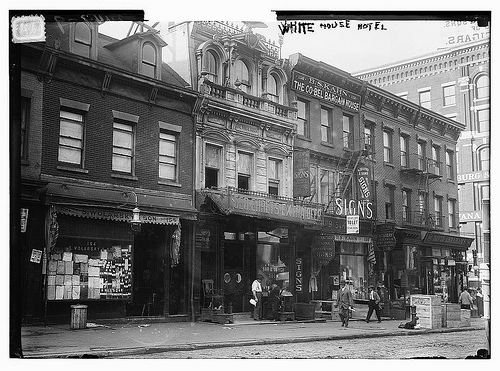

Canal Street c. 1910 (Source: Library of Congress via Flickr Creative Commons)

New York is constantly reinventing itself: bigger and brighter buildings are always in the works; there’s a new “hot” neighborhood before you have the chance to get dinner reservations at the last one. It’s perhaps no surprise, then, that we give our history less weight than the other great western cities of the world. While London and Paris treasure and trumpet their past, New Yorkers tend to eschew theirs: we pass street signs every day that herald the forefathers of our city, without even knowing what they mean, but in many ways they’re one of the last public indicators of those who came before and their influence. As it is, they can act as a road map through the history of this city and of America itself – it just takes a little investigating. Here we present the backstories on three major downtown avenues that you probably never thought twice about.

Jonah Schimmel’s Knish store at the corner of East Houston and Forsyth, c.1931

Houston Street

Contrary to what you may think, the esoteric New York pronunciation of this major thoroughfare is not simply a mechanism to expose uninitiated tourists. It is “HOW-ston” after William Houstoun, a lawyer from Savannah, Georgia who was part of the Georgia delegation to the Continental Congress, and to the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Houstoun married Mary Bayard, a New York girl whose father, Nicholas Bayard, owned huge swathes of land in the modern-day East and West villages. Bayard named the busy road that cut through their land after his southern son-in-law. Bayard’s got his own eponymous street in Downtown Manhattan that runs a block south of Canal between Bowery and Baxter.

The extra “u” was dropped sometime around the early 1800s, but the pronunciation stuck (interestingly, there is also a Houstoun County in Georgia which is also pronounced “HOW-ston.”) The city in Texas is pronounced “Hew-ston” after Sam Houston, the first Governor of that state, and the only Governor of a future Confederate state to oppose secession during the Civil War.

Delancey Street c. 1907

Delancey Street

Running from the Williamsburg Bridge to the Bowery (where it turns into Kenmare Street), Delancey is a major crosstown thoroughfare named for the formerly stupendously wealthy De Lancey family. It was originally a lane that ran near the northern edge of the De Lancey estate, which covered what are now some 120 blocks on the Lower East Side, and was one of the largest pieces of property on Manhattan. The De Lancey’s were a French Huguenot family and one of the richest in pre-Revolutionary New York. James De Lancey, the patriarch, was lieutenant governor and Chief Justice of the British Colony of New York before he took the wrong side during the war, and his loyalty to the crown cost him his land.

In later years Delancey Street became a major shopping street – fairly upscale in the early part of the 19th century and much more immigrant-friendly in later years, serving Chinatown, the Lower East Side and Little Italy. It’s very possible that when Lorenz Hart wrote the line “it’s very fancy/ on old Delancey Street” in his song “Manhattan” that he was joking.

Canal Street El Station c.1930

Canal Street

In the 1700s there was a 48-acre fresh water pond just southeast of the present-day corner of Broadway and Canal Street, known as Collect Pond. In the early bucolic days of the city it was used for recreation and as a reservoir, but soon enough industries began dumping waste there (including a slaughterhouse owned by Nicholas Bayard of Houstoun street fame), and the water quickly became contaminated. In 1807 the city decided to drain the pond by widening a small spring that ran from the pond to the Hudson River. The path along this canal was known as Canal Street. In the 1820s residents began complaining about the foul smell, so the canal was paved over and Collect Pond was filled in.

The landfill was very poorly constructed and the resulting poor drainage, shifting foundations, and unpaved streets forced most of the middle class families to flee the area. Canal Street became the northern border of the area known as “Five Points,” a disease-infected, crime-ridden slum only rivaled by London’s East End for population density, prostitution, unemployment, child mortality and murder.

Related: