“Let’s face it. When it comes to their trash, New Yorkers just don’t want to see it in the morning.”

Those words by Kathryn Garcia, Commissioner of the NYC Department of Sanitation, may ring true for some of us, but New York City’s waste has become top of mind for local residents across the boroughs. No longer a topic reserved for environmental activists and persnickety block associations, the Department of Sanitation and its waste management system have become a more relevant and more visible part of city life under Garcia’s leadership. Garcia, an incisive and ambitious manager appointed by Mayor Bill de Blasio in 2014, is at the helm of the largest municipal waste management agency in the world.

The rising public interest in and civic concern for NYC’s trash was no more clear than at The Future of Waste, the first in a series of Open House New York events that will explore New York City’s current waste system and its plans for the future. The event, held at the SVA Theater last week, was sold out and attended by a diverse mix of New York City lifers, urban infrastructure wonks, armchair environmentalists and spritely, bike helmet-toting progressives. The focal point was a presentation given by Garcia on 0X30, the DSNY’s innovative plan to reduce New York City’s contributions to landfills to zero by 2030.

Currently, the average New Yorker throws away 25 pounds of trash a week — 16 at home and nine at work. Over the course of a year, New York City produces 14 million tons of trash. Getting from 14 million to zero is a daunting prospect, but Garcia laid out cogent and optimistic plans for a more sustainable future.

The History of Waste Management in NYC

New York City’s history with trash is deep and storied. New Yorkers in the 18th and 19th centuries were encouraged to throw their trash into the East River to shore up fill for underwater sections of Lower Manhattan. In 1885, the city opened the nation’s first trash incinerator on Governor’s Island. Later in the 1950s and 60s, city planner Robert Moses used trash to fill swamps and rivers to develop parkland, fairgrounds, and airports. Over the course of the 20th century, Staten Island’s Fresh Kills, which opened as a temporary landfill, metastasized into the largest dump in the world sprawling across 2,200 acres.

(Source: Fresh Kills Park)

As late as the 1960s, there were 11 unfiltered trash incinerators burning our garbage and belching out black smoke. When Fresh Kills closed in 2001, there was no plan for the future of waste in New York City. The absence of a waste management agenda led to the proliferation of private waste transfer stations heavily concentrated in Sunset Park, North Brooklyn, the South Bronx and coastal Queens. The tension between the residential quality of life and the infrastructure needs of our waste management system comes to a head in the neighborhoods surrounding the transfer stations. These areas see thousands of diesel trucks rumbling through their streets to carry our trash out of the city. Currently, we cart our trash from these waste transfer stations to landfills as far 650 miles away, an efficient and costly process that is at odds with the goal of getting to zero.

The Birth of Recycling in NYC

With any vast infrastructure system, there are many moving parts and New York City’s waste management system is no different. Just as we move forward in one direction, other initiatives take place moving in another direction. At the same time that our reliance on waste transfer stations and out of state landfills was growing, local initiatives were under way to improve our city’s relationship with trash and inch us towards a more sustainable future. As early as the 1980s, New York City was launching public recycling programs. At the outset most of these initiatives were small community-based programs, but as the decade progressed local environmentalists began to advocate for more comprehensive, city-wide recycling. In 1989, a bill, dubbed “the New York City Recycling Law” was passed, setting an example for major cities across the world to engage in full-scale recycling efforts. Despite this early innovation, our relationship with recycling and responsible waste management has been pocked by big city issues – density, housing infrastructure, public adoption, flagging political support and limited space.

Getting to Zero

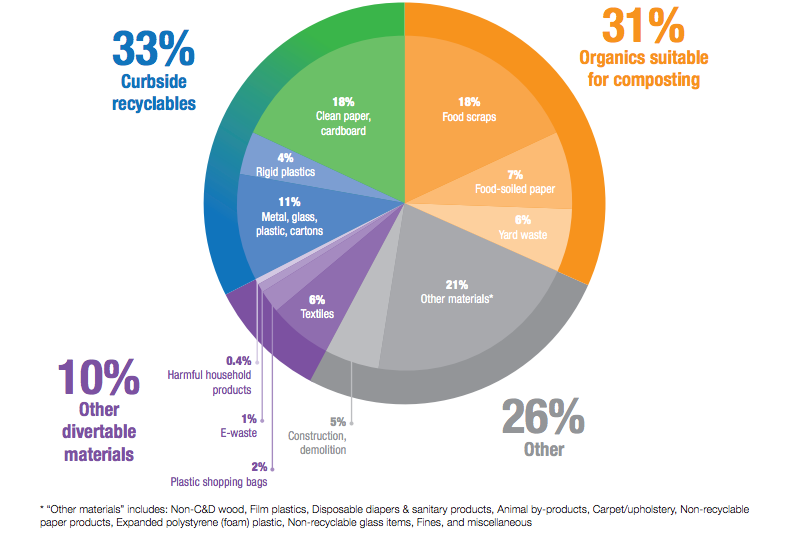

In her presentation, Garcia outlined that to cut down our waste we first have to understand what we’re currently producing. Currently, a third of New York City’s residential garbage is recyclables, a third is organic waste, a quarter is labeled as “other” and the remaining 10 percent is electronics, which is the fastest growing share of our waste composition. (See chart below for details.)

(Source: NYC Waste Characterization Study)

Most recently, the city has made innovations around our organic materials disposal process. Organic materials refer to food scraps, food-soiled paper, and yard waste. According to Garcia, New Yorkers need to start thinking of these materials not as waste, but as resources. If disposed of properly, your pizza sauce-soaked paper napkins, your lemon rinds, and your faded carnations can be used to create compost and create renewable energy – both vital byproducts that will get us to zero.

(Newtown Creek Waste Water Treatment Facility in Greenpoint. Source: Victoria Belanger)

A major factor in getting us to zero is a joint private and public partnership between the DSNY’s organic waste collection program and National Grid’s waste water treatment plant at Newtown Creek in Greenpoint. Since launching its first organic waste collection program in 2013, the Department of Sanitation has expanded collections nearly tenfold and now includes approximately 300,000 households and nearly half of all NYC public schools. In April 2016, DSNY reported collecting 36.7 tons of organic material. Its ambitious goal is to make curbside or drop-off programs available to all residents by the end of 2018.

Where NYC Garbage Goes

Now that the city is collecting compostable materials, however, does not mean there’s any less waste. In order to deal with the nearly 40 tons of organics that are being collected, DSNY has recently launched partnerships with both National Grid and several other private organics recycling facilities to convert the food waste from New Yorker’s kitchens and yards into material for renewable energy.

At six waste transfer stations (located throughout the city with three sited in North Brooklyn), our organic waste is processed into a compound referred to as a BioSlurry that then is shipped to the Newtown Creek wastewater treatment facility, where it is converted into methane gas which can be used for electrical power generation and heating in the form of natural gas.

Although the initial results look promising, there’s a long road ahead. As ever, progress in one direction does not necessarily spell progress in another. Although local residents have been receptive to composting initiatives, many residents take issue with the construction of transfer stations, where trash collected by garbage trucks gets dumped, compiled and then shipped out to landfills outside the city. As a result, transfer stations and the area surrounding them see a lot of truck traffic (both from DSNY trucks as well as 18-wheelers that then carry the waste out of the city) and can omit some serious odors. Anyone who’s hung out in Red Hook Ballfields in the summer knows how intense the hot garbage smell can be. As a result of the traffic, the smell, the general unsavoriness of the stations and the collateral issue of increased rates of asthma due to truck traffic, many neighborhoods take a staunch NIMBY attitude to the construction of transfer stations in their communities.

Mixed Public Support When Garbage Gets Dumped Nearby

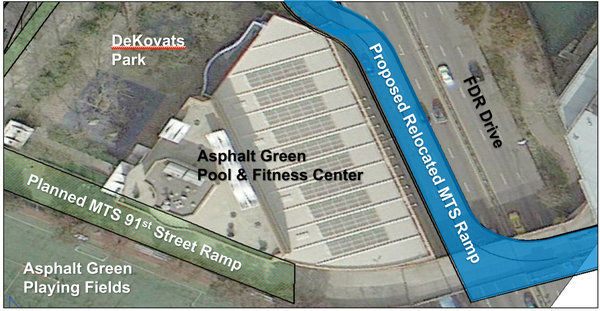

(Overview of the 91st Street Marine Transfer Station, Asphalt Green Recreation Center and York Avenue. Source: A Walk in the Park)

Despite the understandable opposition, the presence of local transfer stations is a fundamental part of New York City’s waste management system. One transfer station that has caused a particular local uproar is the Marine Transfer Station on East 91st Street and the FDR Drive in Yorkville. This marine transfer station is a key component of the city’s solid waste management plan, which includes a mandate to switch from long-haul garbage trucking to a system of marine and rail transfer stations spread throughout the five boroughs. According to Garcia, the MTS on East 91st Street is anticipated to collect waste from four districts in Manhattan helping to reduce the city’s annual greenhouse gas emissions by 34,000 tons and cut annual truck travel by 60 million miles.

(Proposed relocation of main entry ramp. Source: A Walk in the Park)

Frustrated, NIMBY-leaning neighborhood advocacy groups have alleged that the primary entrance to the transfer station on 91st Street and York will cause increased traffic and pose danger to pedestrians and children crossing the avenue on their way to the Asphalt Green recreation center. Despite the pushback, the city announced plans to move forward with construction of the MTS with the caveat that the main entrance to the facility is moved to a block north to 92nd Street. Although this adjustment was welcome by many community advocates, it also pushes the main entrance closer to the NYCHA housing complex located on 93rd Street and First Avenue. This game of Parcheesi, moving the entrance to appease different key players, is the name of the game with many large infrastructure projects, regardless of the long-term gain it promises.

Challenges of Dense Vertical Living

With any vast infrastructure system, there are many moving parts and New York City’s waste management system is no different. Just as we move forward in one direction, other initiatives move in another direction. Although slow progress has been made with the construction of locally sited marine transfer stations, there are many systemic infrastructure issues that impede our waste management process.

One major issue has to do with the kinds of buildings and apartments we live in. In New York City, our apartment buildings are tall and packed with units, while the apartments themselves are small and the kitchens smaller still. It’s nearly impossible to fit a single trash can in the typical New York City kitchen – let alone three (one for papers, one for plastics, one for general trash) and make room on the counter for the compost bin. These constraints make adoption of proper recycling habits difficult even for the most well-meaning New Yorker. On top of space issues within our own homes, many tall apartment towers have centralized garbage rooms in the basement, which further challenges adoption by requiring residents to schlep up and down the elevator – or worse — up and down the stairs in a walk-up just to get their garbage out of their apartments. The more of a hassle it is, the more likely we are to throw the metaphorical towel in and simply dump everything in the same trash can and call it a day.

> Tips on How to Recycle in Your Tiny Apartment

Garcia pointed out that New York City is one of the few major metros to have dual-stream recycling as opposed to single-stream recycling, which allows residents to throw paper and plastic into the same bin and then have the sorting take place at waste processing plants. This sort of practice alleviates residents of the small burden of sorting trash manually, which in the long run could promote better recycling habits in New York City.

The Commercial Carting Quagmire

The distinction between commercial and residential garbage disposal in New York City further complicates the city’s waste processing infrastructure. Where the DSNY is responsible for residential collection, a cabal of private contractors (formerly many of them run by the mob) controls commercial waste disposal. Together, the two entities shell out $2.3 billion to get rid of all the trash we produce on annual basis. What it costs for these entities to collect trash is twice as high as what it costs to actually dispose of it, suggesting that there are issues and inefficiencies with how the collection process works and also simply that there is a huge and constant demand for collection. As result of the inefficiencies of our city, New York City pays more per ton of trash than other cities.

Part of the issue with the volume of trash that we are producing and subsequent demand to have it collected is that New York City is one of the few large urban centers that relies entirely on tax dollars to pay for residential trash collection. In other cities, residents pay fees for bag, bins and are charged by the volume of trash they produce.

As Garcia drew her presentation to a close, she made it clear that the biggest challenge to address in getting New York City to zero landfill contributions will be to change the mindset. The DSNY can launch a whole gamut of initiatives and programs, but their public reception and their ultimate impact come down to the individual level and whether we are willing to make changes to our daily lifestyle, habits, and communities to consume and dispose of more efficiently. Based on the size and enthusiasm of the crowd, it seems like New Yorkers want to improve local waste disposal habits and practices. Whether the enthusiasm of all small group of engaged residents, activists, and politicians can effect widespread change is yet to be seen, but if the history of the local recycling law is a precedent, we have reason to be hopeful.

Check out Open House New York’s website for more information on upcoming Getting to Zero events.

Related