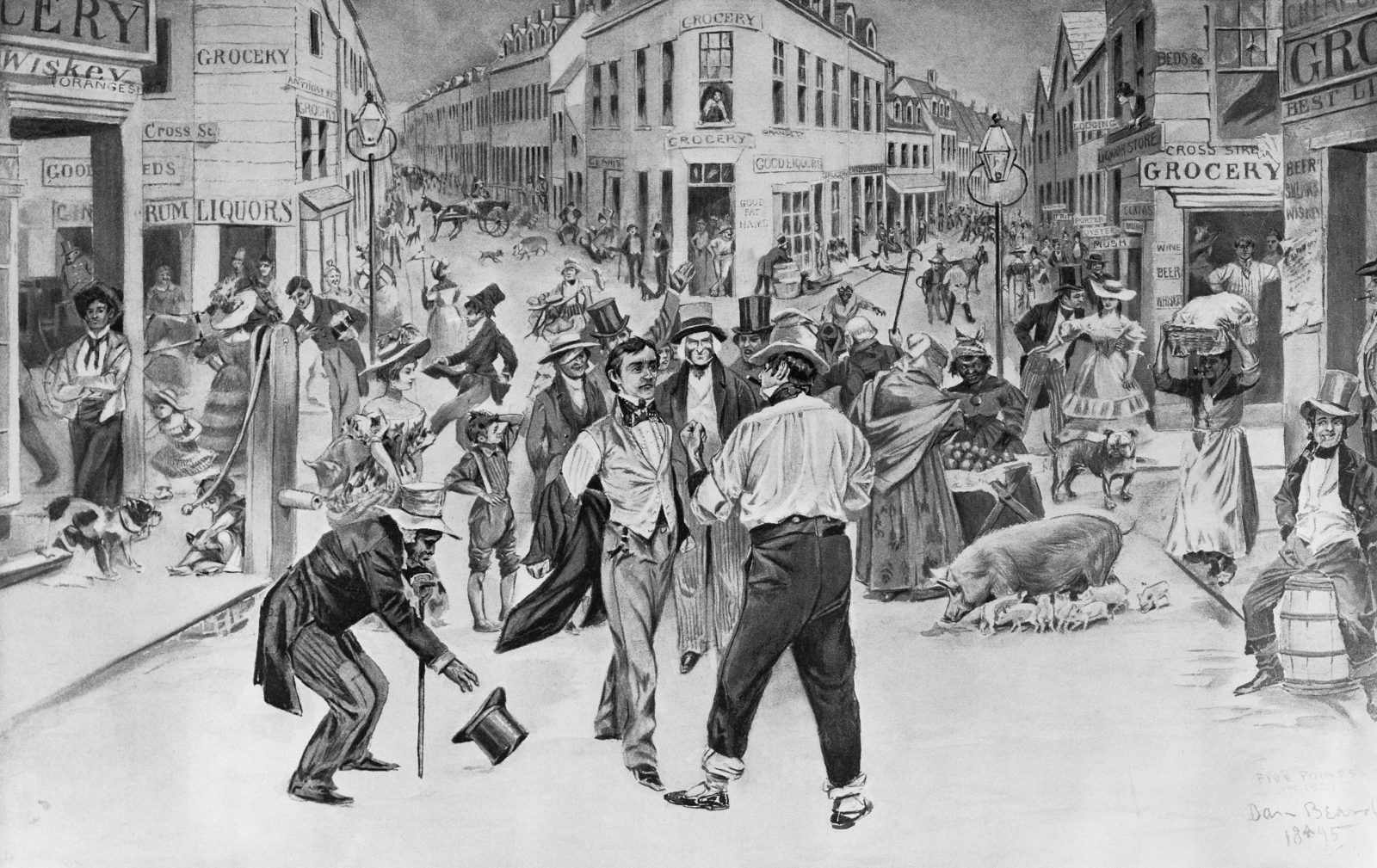

An encounter between a Swell and a Bowery Boy in the Five Points neighborhood of NYC, circa 1827. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

What’s the most dangerous and notorious neighborhood in the history of New York City? You might think it’s the Times Square of the 1970s and ’80s — an area certainly famous for its debauchery. But you’d be wrong. By all accounts, the roughest place in all of NYC was an area known in the 1800s as the Five Points. This neighborhood’s assemblage of thieves, brigands, prostitutes, murderers and fiends would put even “The Deuce” to shame. So how did the Five Points come to be?

Where Is the Five Points NYC Today?

The Five Points neighborhood was located near today’s Columbus Park, between the Manhattan Civic Center and Chinatown. It was so named because three streets — Orange, Anthony and Cross — intersected there, producing five corners, or “points.” The closest intersection to the Five Points today is where Columbus Park meets Worth and Mulberry streets.

Five Points NYC: How It Began

The bad vibes around the Five Points began even before it was developed. The area was originally a body of water called Collect Pond — an important hydration source for colonial New York. But by the Revolutionary War, the pond had become polluted and unusable. Its water was drained into the Hudson River through the canal that became Canal Street, and by 1812, the pond was cheaply filled in.

A map from the mid-1800s showing Manhattan streets overlaying the former Collect Pond. The Five Points was the X-shaped intersection at the lower right corner of this map. “The Tombs” was a nickname given to the New York City jail. (Archive Photos/Getty Images)

The brick and wood houses built on the former pond were unstable, however, and tended to sag and lean. The area began attracting residents who couldn’t settle anywhere else — people of little means, people who preyed on those with little means. The center of the growing Five Points neighborhood was a 1792 brewery on Cross Street first known as Coulter’s Brewery, later just the Old Brewery. It was the site of countless heinous crimes. Inevitably, gangs such as the Plug Uglies (they wore plug hats), the Dead Rabbits, and the Bowery Boys formed for mutual protection.

Apartments for Rent in Chinatown and Civic Center Under $3500 Article continues below

How Bad Was the Five Points, Really?

Kenneth Dunshee described the Five Points in 1952’s “As You Pass By,” a history of the volunteer firefighting units that predated the FDNY:

“The Old Brewery was a five-story building, old and dilapidated. Along one wall an alley led to a single large room in which more than 75 men and women of assorted nationalities and races lived together. This was the Den of Thieves. The name was appropriate. Along the other wall ran another filthy lane called Murderer’s Alley, worse than the first.

“Upstairs there were about 75 other chambers, housing more than 1,000 people … men, women and children. The section was a warren, with underground passages and murderous cul-de-sacs, into which the police dared venture only in large numbers, for the Old Brewery for a period of more than 15 years averaged a murder a night.

“Five Points was too tough, too unlawful, too unsavory to last, even in the New York of a century ago. The Old Brewery was razed, the last of the gangs destroyed. Today [in 1952] it bears little resemblance to the bull-baiting, rip-roaring hell it was in 1850.”

The Old Brewery was the center of the Five Points NYC, and for a time averaged a murder per night. This view is from around 1850. (Corbis Historical/Getty Images)

Charles Dickens also portrayed the Five Points in 1842’s “American Notes For General Circulation”:

“What place is this, to which the squalid street conducts us? A kind of square of leprous houses, some of which are attainable only by crazy wooden stairs without. What lies behind this tottering flight of steps? Let us go on again, and plunge into the Five Points. This is the place; these narrow ways diverging to the right and left, and reeking everywhere with dirt and filth.

“Such lives as are led here, bear the same fruit as elsewhere. The coarse and bloated faces at the doors have counterparts at home and all the world over. Debauchery has made the very houses prematurely old. See how the rotten beams are tumbling down, and how the patched and broken windows seem to scowl dimly, like eyes that have been hurt in drunken forays. Many of these pigs live here. Do they ever wonder why their masters walk upright instead of going on all fours, and why they talk instead of grunting?”

Remnants of the Five Points NYC Today

By the 1920s, most of the vestiges of the old Five Points had been replaced by court houses and parks, and by the 1960s, high-rise apartments had obliterated the last of its little wood frame and brick buildings. But there are still a few remnants of Five Points around for the urban explorer to ferret out.

Columbus Park. (Kevin Walsh)

Columbus Park, on Worth Street Between Baxter and Mulberry

Columbus Park was built in 1887 at the heart of what was Five Points, replacing some of its old tenements. The expansive park was designed by Calvert Vaux, co-creator of Central and Prospect parks. After going by a variety of other names, it was named Columbus Park in 1911 in honor of the many Italians settling nearby.

Mosco Street. (Kevin Walsh)

Mosco Street, Chinatown

Mosco was once Park Street and before that, in the mid-1800s, it was Cross Street; it cleaved through the heart of Five Points. Park Street once ran a full five blocks, from Centre and Duane northeast to Mott Street, with only the easternmost block still there. Civic Center’s court houses (familiar from their appearance on TV shows like “Law and Order”) and Police Plaza have replaced the remainder of the street.

William Poole gravestone in Green-Wood Cemetery. (Kevin Walsh)

William Poole Gravestone, Landscape Avenue, Green-Wood Cemetery

A small granite headstone displaying the name of William Poole (1821-1855) was placed in Green-Wood in shouting distance of Horace Greeley’s gravesite on February 13, 2003. Indelibly portrayed by Daniel Day-Lewis in Martin Scorsese’s “Gangs of New York,” as well as in many previous books and films, Poole was a real-life butcher by trade who served as an enforcer for the Know-Nothing Party — in other words, a brawler and a thug.

Lower Manhattan Apartments for Sale Under $1M Article continues below

Poole’s New York Times obituary described him as having a disposition “not of the most peaceable and forebearing kind.” He grew up as a member of the Bowery Boys, a violent street gang described by era chronicler Herbert Asbury as “the most ferocious rough-and-tumble fighters that ever cracked a skull or gouged out an eyeball.” Poole was a deadly knife fighter; his nickname “The Butcher” was not bestowed primarily for his legitimate profession.

Scorsese’s film accurately portrayed some of 1800s New York and the Five Points, but it also took liberties, such as shifting the action from Poole’s 1850s heyday to the Civil War era a decade later. Pool was truly recognized by some as a hero, however: his funeral procession to Green-Wood Cemetery attracted thousands.

Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)