NY Mets’ Citi Field in Flushing. (Source: slgckgc via Flickr Creative Commons.)

Beyond the claims of grandeur we New Yorkers are known to make, here is a statement of sheer fact: In the past century, only New York City has had four — count ‘em four — major-league teams in four different ball parks, in four separate boroughs of the city. (Sorry, Staten Island.) These teams sprung up in far-flung neighborhoods with their own discreet charms, even as teams moved to California, or across the street. Did the Dodgers, Giants, Yankees and Mets take their character from their neighborhoods? Look at NYC baseball history, and you could sure make a case they did.

The Brooklyn ‘Trolley-Dodgers’

When Casey Stengel, a brash young outfielder from Kansas City, arrived in the major leagues near the end of the 1912 season, the Brooklyn team was playing in ramshackle Washington Park in Park Slope, between First and Third Streets and Third and Fourth Avenues. It is now a parking and storage area for Con Edison, the New York utility company, but Old Stone House, a conservancy group in Park Slope, has some terrific historical data and photos.

Washington Park, where the Brooklyn Dodgers played from 1883 through 1912. (Source: Old Stone House)

Stengel figures prominently in the history of New York’s major league teams: The greatest character in baseball illustriously played for or managed the Dodgers, Giants, Yankees and Mets.

Marty Appel, who has written a fine biography of Stengel, calls the Dodgers’ first park in Park Slope “foul-smelling.” By the time young Casey made it north for the 1913 season, the team had moved to its rather grand new home in Flatbush, an old Dutch neighborhood. This is where the “real” Dodgers were born.

The team was originally called the “Superbas,” but the electrified trolleys gave the fans and the team a nickname — “Trolley-Dodgers.” The shortened version became the official name of this National League team as Casey and the rest of the Dodgers melded with their Brooklyn home.

Ebbets Field as the Heartbeat of Flatbush

The Dodgers would wind up playing 45 seasons at Ebbets Field, the ballpark with the Italianate Rotunda behind home plate. It was located at the intersection of McKeever Place and Sullivan Place, with a high, right-field wall that backed onto Bedford Avenue. This thoroughfare is the longest street in Brooklyn, running 10.2 miles from Greenpoint (pronounced “Greenpernt”), and over the glacial spine of Long Island, down to Sheepshead Bay.

Flatbush bustled with life. Aging Brooklynites still tell stories about spotting Jackie Robinson or Gil Hodges, who married an East Flatbush girl. Many Dodgers with families rented places in Bay Ridge in southwest Brooklyn. Jackie Robinson’s homes have been landmarked.

My earliest excursions to Ebbets Field involved three separate subway lines from adjacent Queens County. That was in the 1940s and early 50s, and I’d emerge from the underground to a daylight tangle of rabbit-warren hot-dog dens. Nothing grand but this was, a real drumbeat of life and baseball, pulsing with Brooklyn’s ancient Dutch-Irish patois. “Brooklynese” is best illustrated by the foreign-language-sounding threat Dodger fans used to hurl at visiting players (except the deified Stan Musial): “Berl yez in earl.” (Say it out loud; it will come to you.)

Playing Ball in the Melting Pot

In the Brooklyn of the Dodgers, generations of immigrants thrived in apartments emitting the aromas of home cooking. When mothers wanted sons to stop playing stickball in the street and come home for supper, they leaned out the window and hollered. All mothers. All sons. (Not sure what daughters were doing.)

When I went to junior high in the leafy Jamaica Estates section of Queens, half my friends at Jamaica High School had been abducted by their parents and taken from Brooklyn to foreign places like Forest Hills, Kew Gardens and Jamaica Estates and beyond, speaking longingly of the old neighborhoods they left behind.

Alas, the Dodgers left for Los Angeles after the 1957 season. The villains and causes are too numerous to enumerate here. If you can stand schmaltz (technically, chicken fat, but essentially nostalgia) listen to Neil Diamond’s tear-jerker, “Brooklyn Roads” — about white flight to the suburbs, although it doesn’t say so.

Brooklyn remains the Mother Ship, with several million people from Africa and the Caribbean and now a species known as hipsters, which I will let somebody else explain. More than half a century later, when I visit the lovely Botanical Garden or Brooklyn Museum a few blocks away, my head spins like a compass toward the site of Ebbets Field (below), now a housing complex.

New York Giants at the Polo Grounds in Manhattan

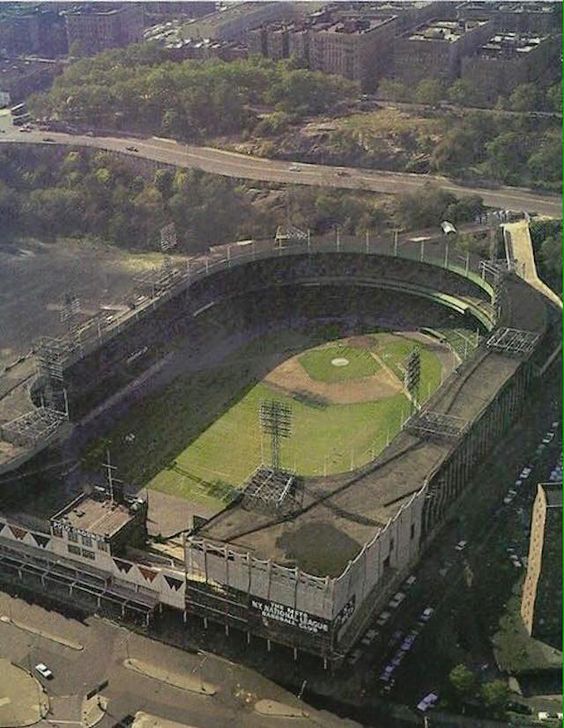

Another ballpark and neighborhood faced the realities and myths of white flight. The oval Polo Grounds, situated below Coogan’s Bluff in Upper Manhattan, facing the Harlem River and the Bronx, was built for baseball, not polo.

It held the haughty New York Giants, the great team of the first two decades of the 20th century, when games were played in mid-afternoon to accommodate a “carriage trade” of stock brokers and other swells. Families named Whitney and Walker (ancestors of two presidents named Bush) owned bits of the Giants. (Casey Stengel later played for the Giants and met his wife, Edna, at the Polo Grounds.)

The Polo Grounds was built for baseball, despite its huge oval size.

There wasn’t much room along the river, but up above was Harlem, mostly black, with high-end areas like Strivers’ Row and Sugar Hill and many less affluent ones, too. After World War II, ball clubs largely depended on fans with automobiles coming back from the suburbs — and the Polo Grounds had minimal parking. The Giants moved to San Francisco after the 1957 season.

The Yankees and Babe Ruth in the Bronx

Meanwhile, a more humble New York team, the Highlanders, moved (from Baltimore) to Upper Manhattan. Then, on April 18, 1923, they moved to a new stadium in the Bronx, made feasible by the slugger Babe Ruth. (Quick trivia: Who hit the first World Series homer in Yankee Stadium? Doddering Casey Stengel, then with the Giants.)

The House That Ruth Built was near the Harlem River, a few hilly blocks below Grand Concourse — the Champs Elysées of the Bronx, so to speak, with artistic flourishes and fine new apartment buildings.

Yankee Stadium has long defined the Concourse skyline in the Bronx.

Yankee fans like Alan Taxerman gladly took the Q-43 bus and two subway lines from East Queens to the Bronx. “There was a grandeur to the area that a 10-year old kid felt, and inside, watching Mantle take BP was very special,” recalls Taxerman, now a lawyer.

“The Bronx was an amalgam of ethnic groups at that time,” Taxerman continues in an email. “You could get great deli, pasta and corned beef and cabbage and Latin specialties, too. Two blocks from the Stadium stood the great courthouse.”

The new Yankee Stadium was built at 161st Street, near the original House That Ruth Built.

Taxerman, who is Jewish, says everybody referred to the Concourse as “the Cohen-Course.” Many Yankees stayed at the Concourse Plaza Hotel. And for a nosh in the neighborhood, continues his Proustian reverie, “Nothing like a Cohen-Course knish. We called them hockey pucks with deli mustard. Oy!”

Generations of Bronxites held weddings and bar mitzvahs at the Concourse — until they moved to Westchester, New Jersey, Connecticut.

That portion of the Bronx became significantly Latino — Kosher delis became bodegas — and life went on. The Yankees won a zillion pennants and Casey, arriving with a reputation as a clown, managed 12 years and won 10 pennants in that majestic “ big ballpark in the Bronx,” as Red Barber called it. (The Yankees have since moved to a new stadium across 161 Street with the sterile ambience of a theme park.)

Goodbye Giants and Polo Grounds, Hello Mets and Flushing

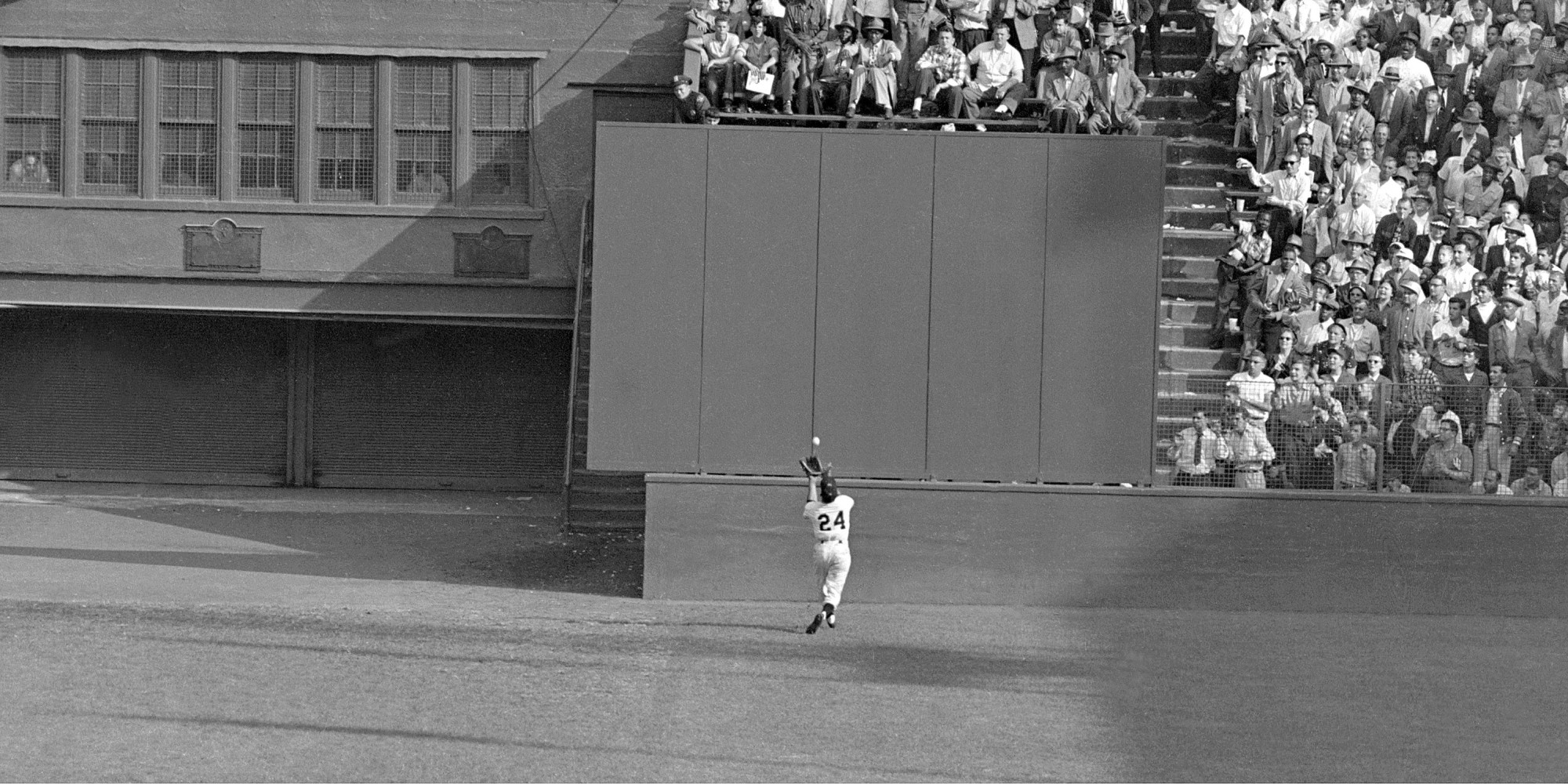

The Polo Grounds was not done — and neither was Casey. In 1962, a new expansion team, the Mets, was dropped into the Polo Grounds while a new stadium was being built in Queens. The manager was … well, you guessed it. The Mets thrived on the funky love of baseball lingering in the Polo Grounds — memories of Willie Mays roaming the vast outfield.

The Catch: Willie Mays made one of the greatest plays ever in baseball in 1954 at the Polo Grounds.

For afternoon games, little boys wandered down the stairs of Coogan’s Bluff and somehow got inside.

In 1964, the show moved to Shea Stadium in Queens, plopped onto the marshy glop at the edge of Flushing Bay, where garbage used to be burned 24/7 (“A valley of ashes,” F. Scott Fitzgerald called it in “The Great Gatsby.”) The World’s Fair throbbed across the street in 1964-65. The Mets were dreadful for six years, mediocre for one, and amazing in 1969. There was no neighborhood around Shea, unless you counted the chop shops — repair shacks for autos, run by hard-edged entrepreneurs.

These days, it is a wonder anybody goes to a ball game, what with the life and the food in various neighborhoods of Queens, near the new Mets’ stadium, named for some bank.

For the last hardy New York ball fans who remember Ebbets Field, the Polo Grounds and the old Yankee Stadium, those were glory days … and glorious neighborhoods. At least, that’s how it seems.

[This post has been edited and republished.]

—

Send your NYC real estate stories and tips to StreetEasy editors at tips@streeteasy.com. You will remain anonymous. And hey, why not like StreetEasy on Facebook and follow @streeteasy on Instagram?