Key Takeaways:

- Due to soaring rents and high upfront costs, New Yorkers earning the city’s average annual wage could afford less than 5% of rentals on the market in 2023.

- Essential workers earning average wages in their occupation could afford less than 1% of rentals in the city in 2023.

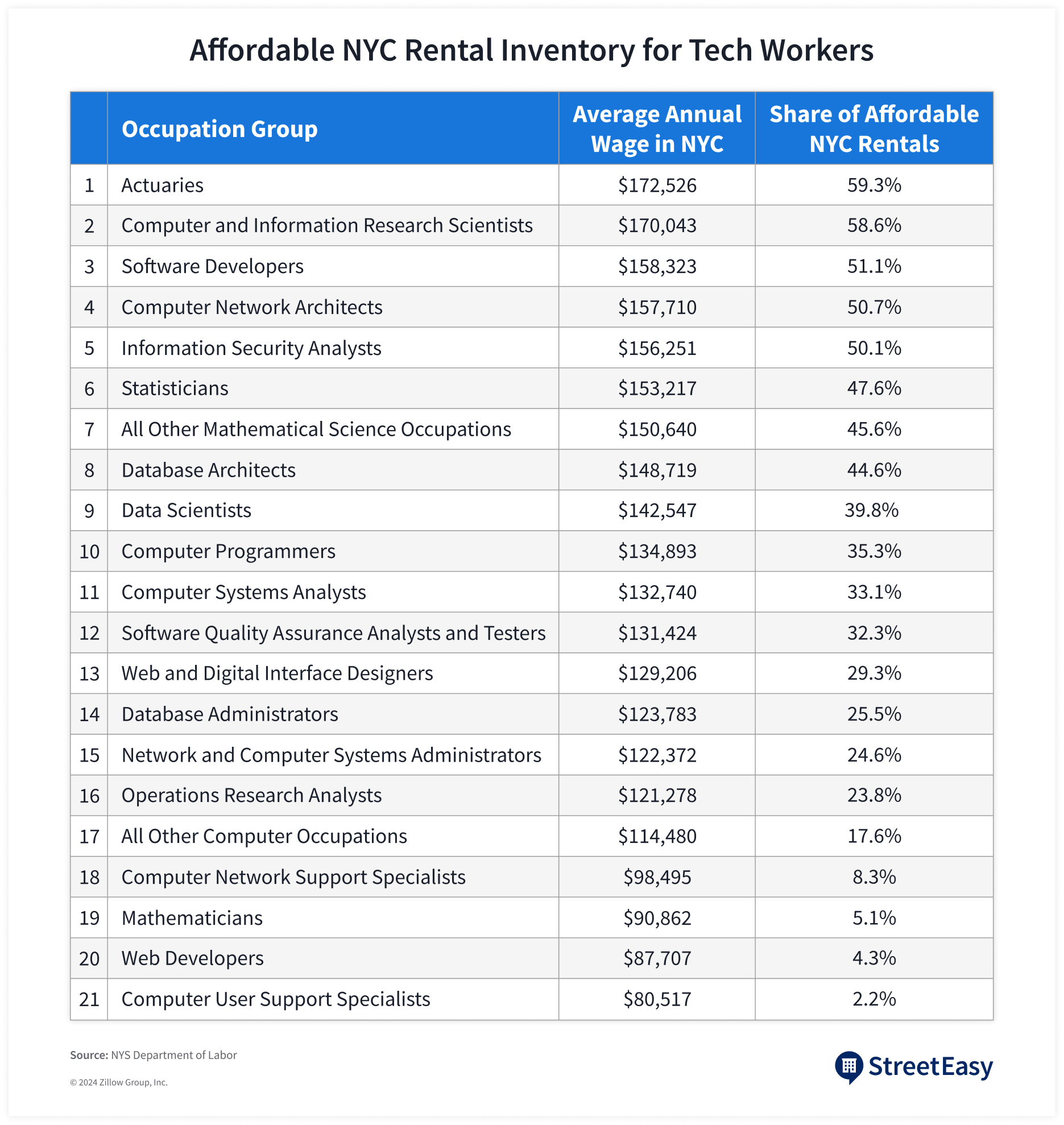

- Tech workers — whose wages are higher than average — could afford about one in three rentals in the city.

- Within the tech sector, a worker earning the average entry-level wage could afford 2.1% of studio and one-bedroom rentals in NYC on their own — that’s one out of every 50 available rentals.

- Targeted zoning reforms to allow modest increases in housing near public transit can unlock an opportunity to create up to 1.1 million new homes.

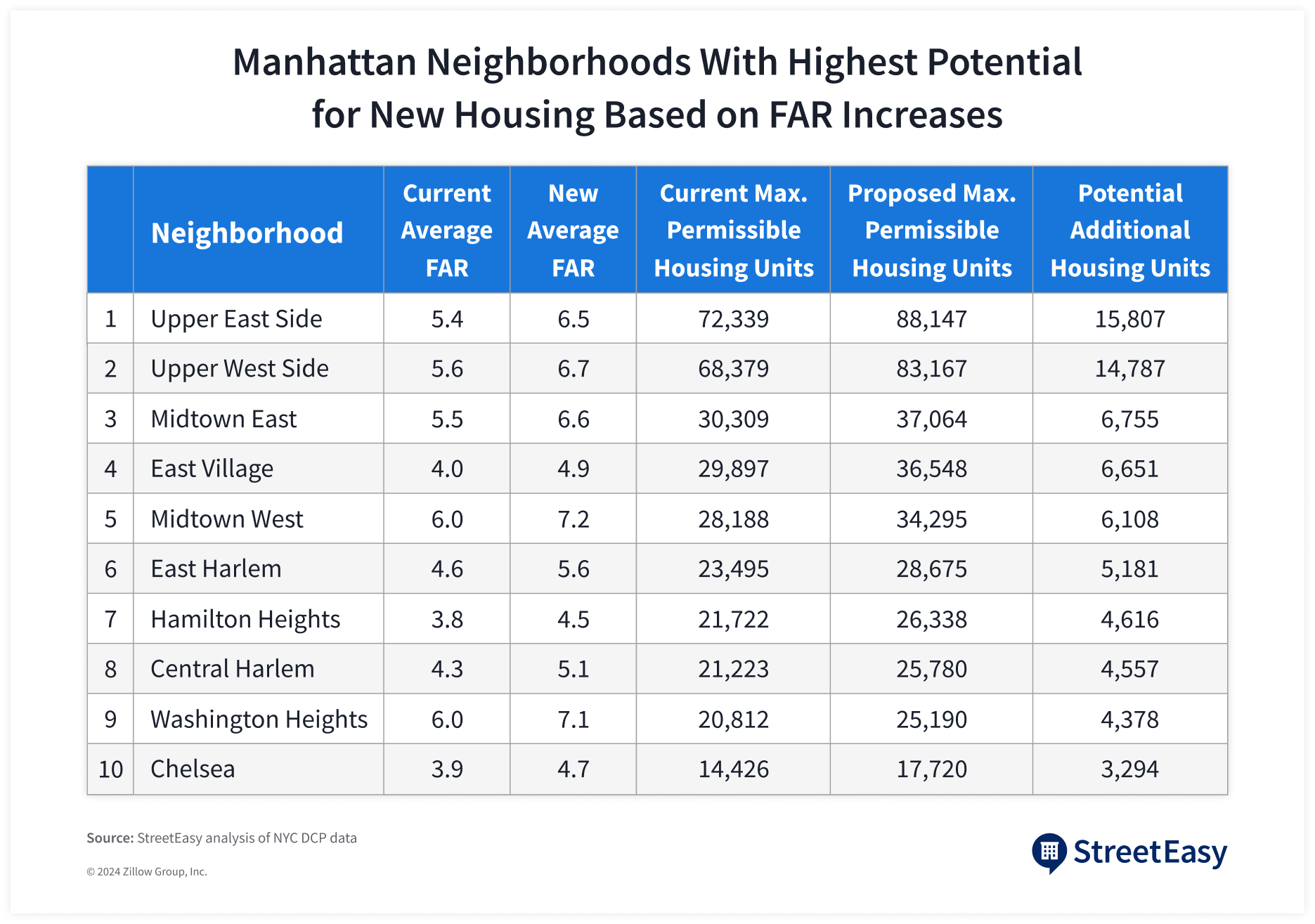

- Increasing the floor-to-area ratio (FAR) by 20% in medium to high-density zoning districts in Manhattan can increase the city’s housing capacity by up to 90,000 units.

- Lowering upfront rental costs by requiring tenants to compensate an agent only when the tenant hires the agent to represent them, and banning the practice of single agent dual agency, will reduce financial barriers to housing and help create a more equitable rental market.

With limited rentals on the market, rents in New York City have been soaring since the pandemic. In 2023, the citywide median asking rent jumped 8.6% from the year before to $3,475 — the highest since 2010, according to StreetEasy® data — but the average wage rose just 1.2% in NYC, as indicated by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Soaring rents relative to average wages make it difficult to find affordable homes. We define “affordable” rentals as those costing less than 30% of gross annual income, the threshold for being rent-burdened as used by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The average gross annual wage in New York City was $88,647 in 2023, according to the New York State Department of Labor. That means a renter making the average income could pay up to $2,216 per month without being rent-burdened. However, StreetEasy data shows only one in ten (10.7%) market-rate rentals in NYC were priced below this amount in 2023. It would take an annual income of $139,000 to comfortably afford the city’s median asking rent, which was $3,475 in 2023.

Spending more on rent leaves a larger hole in renters’ budgets and makes it difficult to save for long-term goals, such as a down payment on a home. However, many New Yorkers don’t have a choice: the latest NYC Housing and Vacancy Survey indicates one in four NYC households spent more than half of their combined income on rent in 2023.

It’s not just soaring rents impacting the housing affordability crisis. The average New Yorker spent $10,454 in upfront costs for a rental in 2023, according to StreetEasy research. Factoring in upfront costs, a New Yorker earning the average annual wage could afford just 4.4% of rentals on the market in 2023 without spending more than 30% of their annual income.

Essential Workers Could Afford the Fewest Rentals in NYC

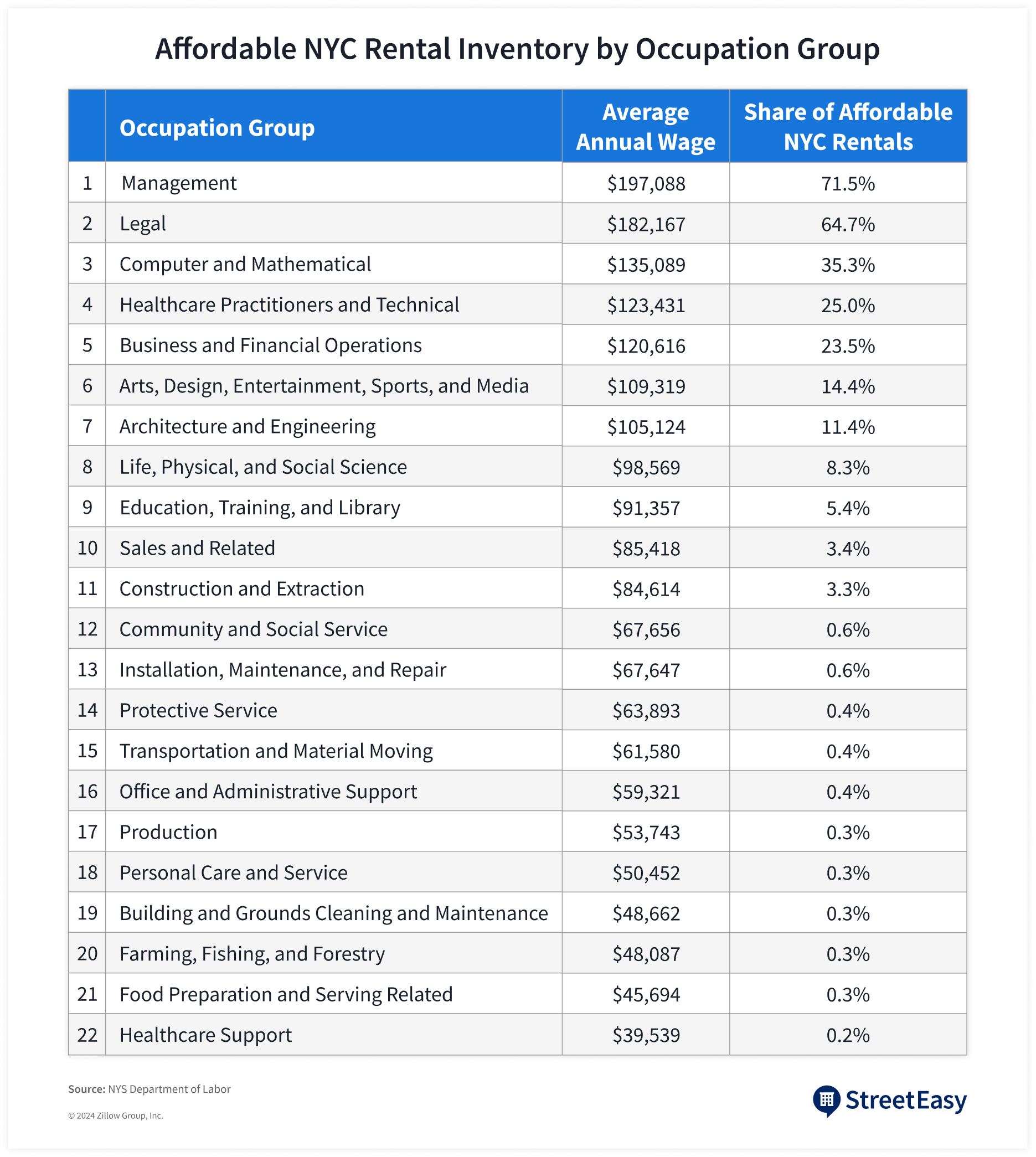

The city’s asking rents remain too high for essential workers across occupation groups like protective services, healthcare support, food preparation and serving, and transportation services. New Yorkers in these occupation groups were paid average wages below $70,000 in 2023, according to the NYS Department of Labor, enough to comfortably afford less than 1% of NYC’s rental inventory in 2023.

Healthcare support workers, including home health aides and nursing aides in hospitals and nursing homes, could afford the fewest rentals of any occupation group. The average annual wage in this field was $39,539, enough to afford a mere 0.2% of the city’s rental inventory. Workers in food preparation and services fared only slightly better, with an average annual wage of $45,694 — enough to afford 0.3% of units last year.

Soaring rents and upfront costs make it challenging for even first responders to find an affordable home in the city they serve. The average annual wage for protective service workers including firefighters, police officers, and transportation security officers was $63,893. Those earning this wage could afford just 0.4% of rentals in the city.

Even Tech Workers Are Struggling to Afford Housing in NYC

High rents are squeezing even workers in the tech industry in NYC, despite a highly competitive labor market. In this report, we consider the computer and mathematical occupations as defined by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics as the most relevant data to reflect tech industry roles (see Methodology section for more on how we define tech workers).

The average annual wage for tech workers in 2023 was $135,089, 52% higher than the average for all workers in NYC, according to the NYS Department of Labor. However, StreetEasy data indicates a worker earning this salary could afford only one in three (35%) rentals on the market in 2023.

The broader tech ecosystem, including tech companies and tech occupations in non-tech industries, contributed to a quarter of total job growth in NYC between 2012 and 2021, a recent Tech:NYC report shows. With 369,000 jobs and $291 billion in economic output, the tech ecosystem accounts for 7% of all jobs and 28% of the total economic output in NYC, underscoring the sector’s significant contribution to economic development across the city.

The growth of NYC’s tech economy has been fueled by the city’s significant investments in nurturing tech talent through various initiatives. These include the Computer Science for All (CS4All) initiative to expand tech exposure at public schools, the Tech Talent Pipeline partnership to increase graduates with tech-related degrees, and efforts to attract both startups and large global companies to open new headquarters in NYC. However, the city’s struggle to create enough affordable housing for not only tech workers but all New Yorkers across all industries threatens its ability to hire, retain, and sustain a robust workforce in the fastest-growing sectors.

For Entry-Level Tech Workers, Affording a Place of Their Own Is Nearly Impossible

Entry-level workers across all occupation groups in NYC are bearing the brunt of the affordability crisis. The average entry-level wage in NYC was $36,721 in 2023, 59% lower than the overall average wage in the city, according to the NYS Department of Labor. These workers could afford just 0.3% of studio and one-bedroom rentals in NYC on their own, StreetEasy data shows.

For those starting their careers in essential services, affording a rental in NYC without being rent-burdened has been especially challenging. A firefighter earning the average entry-level salary of $63,831 could afford just 0.6% of the city’s studio and one-bedroom rentals in 2023. A police officer earning the average entry-level salary of $54,487 could afford 0.4%. A home health aide earning the average entry-level salary of $35,360 could afford just 0.3%.

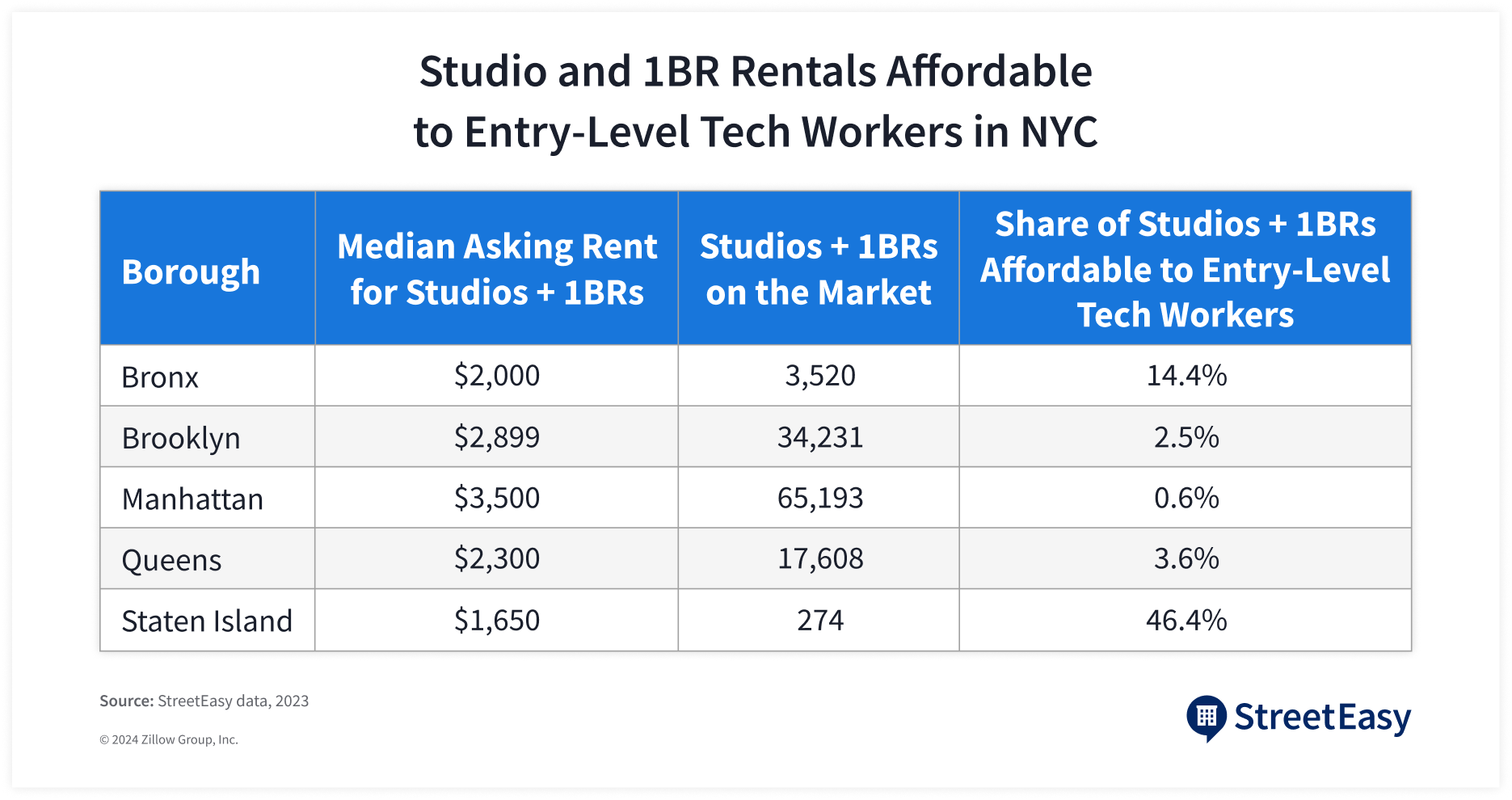

Despite higher starting salaries, finding an affordable rental can be difficult even for those entering the tech sector in NYC. A tech worker earning the average entry-level salary of $75,262 could afford just 2.1% of studio and one-bedroom rentals in the city on their own. Soaring rents encourage recent graduates to take on jobs in other cities with more affordable homes, making it harder for NYC employers to hire and retain these workers eager to start their new careers.

Affordable rentals were hardest to come by in Manhattan, where the median asking rent in 2023 was $4,000 and the median for studio and one-bedroom apartments was $3,500. Even though 87% of the city’s tech sector jobs were located in the borough, according to analysis by the Office of the New York City Comptroller, StreetEasy data shows an entry-level tech worker earning the average salary could afford just 0.6% of Manhattan’s rental inventory without spending more than 30% of their annual income on rent and upfront costs. In Staten Island, 46% of studio and one-bedroom rentals would be considered affordable, but there were just 127 apartments on the market in 2023 as more homes in the borough tend to be owner-occupied.

NYC’s Growing Housing Shortage Increases Costs for Everyone

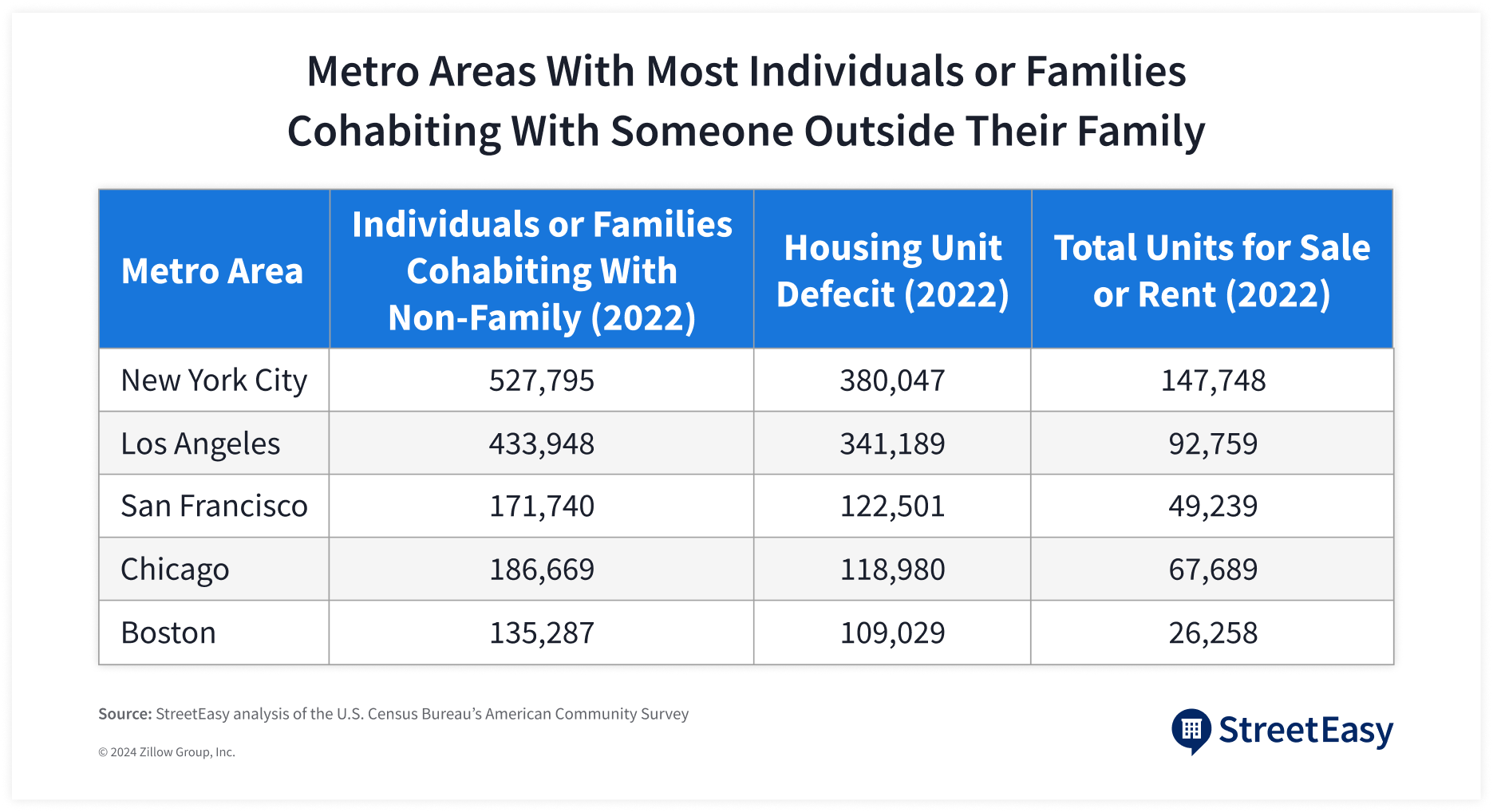

The challenges NYC renters face have been compounded by the fact that the city has not been able to create enough homes to keep up with demand. The metro area’s housing shortage is the worst in the nation, with a deficit of 380,047 homes — more than the San Francisco, Chicago, and Boston metro areas combined, StreetEasy analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) shows.

Over the last 10 years, NYC’s housing shortage has only grown worse. The housing deficit in 2022 was up 51% from 2012, and the acute shortage is fueling competition for homes. In 2022, for each home for sale or rent in the NYC area there were nearly four families in need of a home, compared to two for each home in 2012. This competition has driven up asking rents: since 2020, the typical rent in the NYC metro area has risen 22% to $3,158, according to the Zillow Observed Rent Index.

The worsening housing shortage also keeps New Yorkers stuck in homes they’ve outgrown, or pressures them to combine households with others. In 2022, more than half a million (527,795) individuals or families in the NYC area cohabitated in a home rented or owned by someone outside their family.

NYC’s Housing Capacity Is Limited by Exclusionary Zoning Rules

People of color and lower-income families disproportionately bear the cost of the city’s housing shortage. New York is the second most racially segregated city in the US, and restrictive zoning continues to exacerbate segregation by limiting access to economic opportunity. Since taking effect in 1961 during the urban renewal era, the NYC Zoning Resolution has gone through numerous amendments, but layers of regulation over the past 60 years made it difficult for the city’s housing supply to catch up with surging demand. Building medium-density apartments has become increasingly more difficult, even though construction costs for smaller and mid-sized apartment buildings tend to be less than those for high-rises.

As a result of the 1961 resolution, downzoning swept through neighborhoods in the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island. Zoning districts prioritizing single-family homes kept people of color and lower-income families from moving to these neighborhoods. High-density residential districts were limited to select areas in Manhattan, leading to new housing being created disproportionately in more expensive neighborhoods.

To this day, restrictive zoning continues to stifle housing development across the city. For example, in the decade following a rezoning in 2009 which restricted the height and density of residential developments, the number of permitted housing units in Carroll Gardens fell 77.9%, the city’s analysis shows. In Canarsie, the number of permitted housing units dropped 86.5% following a rezoning to restrict new developments to low-density housing, the city’s report shows.

Low-density zoning districts have created just 28,836 housing units in NYC since 2010, even though they account for almost half (49%) of all residential or mixed-residential zoning. By comparison, medium to high-density zoning districts have created 178,286 units since then — 6.2 times the number of units created in the low-density areas — StreetEasy analysis of the NYC Department of City Planning’s PLUTO and Housing Database shows (see details in Methodology section).

Multi-decade tweaks to the 1961 Zoning Resolution failed to mitigate the Catch-22 situation the city finds itself in, where it must find ways to grow within the confines of restrictive zoning designed to hold down growth. While zoning reform itself won’t solve all of the city’s affordability challenges, more comprehensive but targeted reforms addressing the needs of both low and high-density neighborhoods are necessary to alleviate the housing shortage meaningfully in NYC.

Solutions

Targeted Zoning Reforms Near Public Transit Would Expand the City’s Housing Capacity by up to 1.1 Million Homes

StreetEasy research shows zoning reforms that allow for new housing in underutilized lots near mass transit routes in the city’s outer boroughs would unlock opportunities to create up to 1.1 million more homes — more than enough to accommodate 527,795 individuals or households sharing a home rented or owned by someone outside their family. Our research suggests there is a way to encourage new homes by allowing modest density increases near public transportation, away from areas of higher flood risk due to rising sea levels, and without meaningfully changing the fabric of each neighborhood.

We arrived at this number by calculating the maximum number of new homes that would be permitted by modestly increasing zoning allowances in underutilized sites in “transit-rich” areas within walking distance of mass transit in the outer boroughs, but away from historic districts and high-risk flood areas. We define “underutilized” areas as sites currently zoned as low or medium-density residential districts but are vacant or occupied by single-family or two-family homes. To minimize changing the existing fabric of the city, our analysis assumes that these areas are rezoned only to a degree that is no denser than larger residential buildings that already exist in each neighborhood (see Methodology section for more detail).

This adaptive approach allows underutilized, low-density areas near mass public transit to catch up with the rest of the neighborhood while avoiding over-development via unnecessary upzoning. Despite the surging demand for housing, single-family homes and low-density apartments dominate the boroughs outside of Manhattan. More than half (53.4%) of the lots in transit-rich areas in these boroughs are zoned as low-density, making it impossible to build anything other than single-family homes or multifamily buildings with fewer than five units on average. However, these low-density districts currently account for just 30.9% of the total housing units in transit-rich areas outside of Manhattan.

As a result, asking rents are surging in Queens and Brooklyn as soaring demand continues to drive up prices and limit available inventory. The median asking rent in Queens jumped 13.5% year-over-year to $2,950 in February as housing demand surpassed affordable inventory. In Brooklyn, the median asking rent was $3,330 in February, 4.1% higher than a year ago. Zoning reforms to allow small to medium apartment buildings near public transit would be an inexpensive way to create new housing in inventory-deprived neighborhoods.

For example, Astoria has been a sought-after destination for renters due to its proximity to Manhattan’s midtown office core, but close to two-thirds (64.1%) of the neighborhood’s developable lots near subway stations are locked into low-density zoning. The most common low-density zoning district within walking distance of subway stations is R5, which allows small three and four-story apartment buildings.

Following our adaptive strategy — increasing housing capacity on underutilized lots within this low-density area near mass transit, to the standards of medium-density R7 districts — would add capacity for up to 44,428 new homes in Astoria. The map below lays out these underutilized low-density sites near public transit that could see modest increases in housing capacity. These sites account for 25.8% of all areas within walking distance of subways.

Targeted rezoning will not lead to immediate replacement of existing homes, as any redevelopment requires careful planning to assess community impact and economic feasibility. Instead, it will give local communities the flexibility to create new housing over the coming years based on local demand. Allowing additional small and mid-sized housing near mass transit will help maintain the vitality of neighborhoods and communities — by providing more livable housing opportunities for a wide range of residents, from young professionals to seniors.

Based on our adaptive small and mid-sized housing strategy, the top five neighborhoods with the most potential to increase housing capacity are East New York (Brooklyn), Flushing (Queens), Woodhaven (Queens), Astoria (Queens), and Midwood (Brooklyn). Altogether, these five neighborhoods alone have the potential to create 265,267 new homes, making up 24.3% of the 1,090,226 additional housing capacity across the city under our transit-oriented rezoning framework.

This is aligned with Mayor Eric Adams’ City of Yes proposal which would introduce similar but more tailored zoning changes to low-density districts near mass transit. While the Mayor’s proposal is mostly similar to our approach, it limits zoning changes to sites over 5,000 square feet located on the short end of a block or facing a street over 75 feet wide. The height of new buildings in these sites will be limited to three to five stories.

Remove Parking Requirements and Other Red Tape

Requiring new developments to have off-street parking is one of the most prohibitive policies for building new housing. The current zoning rules require all new buildings to provide a minimum number of parking spots with exceptions given only to affordable housing near public transit. In reality, a majority of New Yorkers do not rely on cars to get around: in 2022, 55% of NYC households did not own a vehicle, the ACS shows.

The high cost of creating off-street parking is well documented. Research shows that parking mandates add 17% to a unit’s annual rent across the nation. In NYC, constructing underground parking can cost $150,000 per space, leading to a unit of housing lost for every 1.2 parking spots, as estimated by Open Plans. The NYC Department of City Planning estimated that each parking unit could add $65,000 to construction costs. The Mayor’s City of Yes proposal would also eliminate the minimum parking requirement for new housing. The proposal will allow developers to build parking only to a degree that can accommodate demand in the neighborhood.

In addition to parking requirements, other provisions such as yard requirements and minimum lot size for developments make it more challenging to increase density in transit-rich areas. Relaxing these restrictive provisions would increase the potential number of new homes that can be created in a neighborhood.

Invest in Public Transit

Investing in public transit would help local communities reap the benefits of increased housing capacity near transit corridors — one of the most effective proposals to spur new housing construction. Public transportation provides essential access to key job centers in the city. Excluding those who work from home, one in two (52%) workers in NYC commuted via public transit excluding taxis, while just one in four (26%) drove alone, according to the 2022 ACS.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) Penn Station Access project will add four new stations in the Bronx along the New Haven line transit corridor by 2027. The new stations will serve existing residential communities in Co-op City, Parkchester, and Van Nest, and cut commute times to Midtown Manhattan by 60 minutes. In Hunts Point and Morris Park, new stations will create vital access points for essential workers in healthcare and food distribution industries. The city’s plan to rezone areas around the newly proposed Parkchester/Van Nest and Morris Park stations would unlock the opportunity to bring nearly 7,500 homes and 10,000 jobs to these neighborhoods, the NYC Department of City Planning estimates.

Increase the Floor-to-Area Ratio in Manhattan

The floor-to-area ratio (FAR) is the ratio of a building’s total floor area to the area of its zoning lot. New buildings must abide by the maximum FAR for their zoning district unless exceptions are granted. Raising FARs in high-cost neighborhoods in Manhattan, combined with additional density for buildings with more affordable units, would incentivize developers to allocate more floor areas to affordable homes.

We estimate that increasing the FAR by 20% in medium to high-density districts currently zoned for residential use will increase the housing capacity in Manhattan by 85,338 from its present capacity of 421,911 housing units. The Manhattan neighborhoods that would see the most new housing opportunities are the Upper East Side, Upper West Side, Midtown East, East Village, and Midtown West, traditionally known for their high costs of new developments. The current regulation provides higher FARs only for developments with affordable independent residences for seniors (AIRS). A far-reaching increase in FAR in these neighborhoods can substantially increase the housing capacity.

Considering high construction costs in these areas, preference should be given to new developments with more affordable housing units. Thankfully, Governor Kathy Hochul and the state legislature just approved new targeted exemptions to the FAR limit in NYC for new residential buildings that include minimum amounts of permanently affordable housing, are not located in historic districts, comply with land use applications, and other requirements. The recent state action would allow the city to change zoning to allow larger residential buildings. Mayor Eric Adams’ City of Yes proposal calls for Universal Affordability Preference (UAP), which would allow a 20% increase in FAR for buildings with all types of affordable and supportive housing as long as the increased floor area is dedicated to affordable units. The proposal will likely make the construction of affordable housing in high-density neighborhoods less expensive, as developers can sacrifice fewer market-rate units to increase the number of affordable units in their buildings.

Strengthen Mixed-Use Zoning Districts With New Tax Incentives

The Midtown South Mixed-Use (MSMX) Draft Zoning Plan, announced by the NYC Department of City Planning this year, would add 4,000 new homes by creating high-density, mixed-use districts in place of manufacturing-centric zones in one of Manhattan’s most central areas surrounded by Bryant Park, Madison Square Garden, and Madison Square Park.

This targeted proposal is a leading example that could be replicated in medium to high-density neighborhoods across the city that have seen demand for industrial or commercial space decline. The new 485x tax incentive for affordable housing, and an extension of the now-expired 421a tax abatement for projects already in construction to 2031, were both approved in New York State’s FY25 budget. This will greatly impact the effectiveness of new zoning plans that seek to enhance neighborhoods through additional housing capacity.

Another obstacle to new construction is the city’s property tax system, which charges large rental buildings with more than 10 units at a higher effective rate than owner-occupied residences. However, the city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing policy, which requires new buildings to set aside a portion of residential units as affordable units below market rate in a rezoned area, increases the financial burden on developers by restricting their ability to recoup the tax costs. Therefore, without the newly approved tax incentives to offset the higher tax burden on rental properties, large increases in new affordable rental buildings in high-density areas like Midtown will continue to be cost-prohibitive.

Reform Upfront Costs for Rentals

Soaring upfront costs have made finding affordable housing even more challenging for NYC renters. StreetEasy data shows the average upfront cost to move into an NYC rental was $10,454 in 2023, up 29% from 2019 before the pandemic disrupted the market. The typical set of upfront costs includes first month’s rent in advance, security deposit, broker fee, and various application fees.

Based on the average upfront cost of $10,454, a renter earning the median household income in NYC ($74,694 according to the 2022 ACS) would have to spend 14% of their annual income to cover the expenses required to sign a new lease. In reality, few renters find themselves ready or able to pay such a large sum — which is more than five times the median cash balance of $2,000 that US renters had on hand at financial institutions in 2022, according to Federal Reserve Board data. The high financial barrier created by upfront costs causes a “lock-in effect,” wherein renters who need or want to move find themselves unable to leave their current apartments.

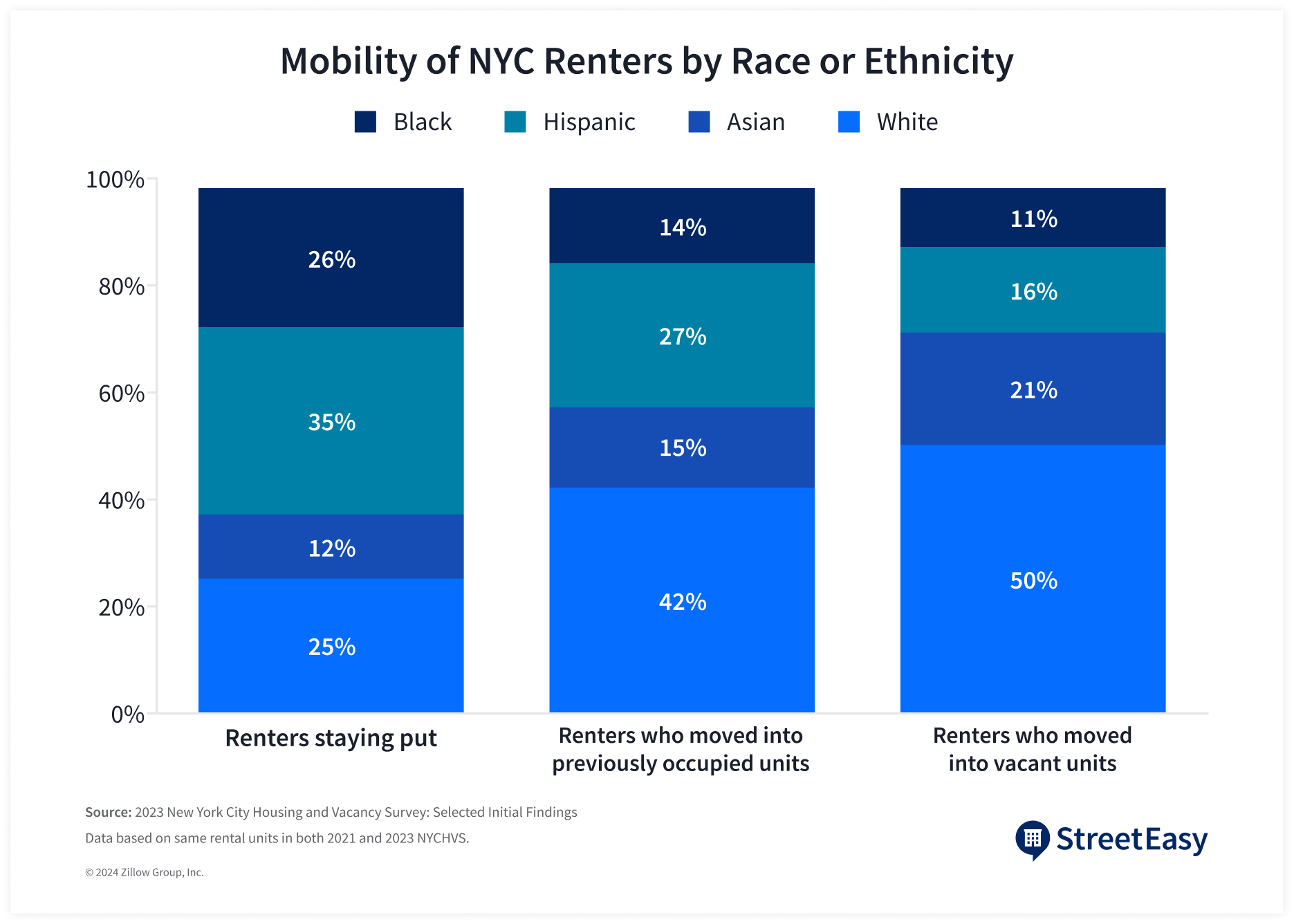

The barrier to mobility also disproportionately affects NYC renters of color. Among households living in the same rental since 2021, 75% are headed by a New Yorker identifying as a person of color, according to the NYC Housing and Vacancy Survey. Meanwhile, those moving into vacant units are more likely to be affluent white renters: 56% of households that moved into a rental since 2021 earned $100,000 or more, and half were headed by a white New Yorker.

Reducing the lock-in effect by lowering upfront rental costs will give all New Yorkers expanded choices in the rental market and improved financial ability to move, whether it’s to be closer to their workplace, accommodate a growing family, or even pay less in monthly rent. A lower barrier to moving will help create a more equitable rental market where renters can afford more homes, and more homes become available as more renters choose to move.

Renters also need transparency around the upfront costs required to sign a lease and awareness that these costs are negotiable. A new policy that would require tenants to compensate an agent only when the tenant hires the agent to represent them and ban the practice of single agent dual agency, whereby the agent is theoretically representing both the landlord and renter in the transaction, would give renters increased transparency as well as significant financial relief from these costs.

Methodology, Definitions, and Data Sources

Tech Workers

Over recent years, the “tech sector” has broadened to include any companies applying the latest technologies to a broad range of traditional industries such as consumer products, transportation, and publishing. As a result, there isn’t a clear consensus on which industries should be included in the tech sector, with a range of organizations such as the Office of the New York State Comptroller and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York using different sets of smaller industries to define the sector.

Tech workers are more easily identifiable by their job duties rather than the industry they work in. The Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) program, published by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), follows the Office of Management and Budget’s Standard Occupational Classification system to define occupations based on their job duties, using data collected by State Workforce Agencies from all US states and territories.

There are about 830 occupations in the OEWS, as described on the BLS website. The computer and mathematical occupation group includes workers often associated with tech, such as software developers, data scientists, and web developers, in addition to some who may not commonly be considered tech workers, such as mathematicians and actuaries. It excludes jobs that may sometimes be considered part of the broader tech ecosystem, such as biotech and engineering occupations outside of computer science. Nevertheless, it is the most suitable proxy for tech workers, as those in this occupation group possess varying degrees of skills in mathematics and computer programming that can be transferred to jobs in the broader tech ecosystem.

Tech Wages

Wages can vary substantially among tech workers in NYC, creating a wide range of housing affordability rates. For example, high average wages are seen among computer and information research scientists, software developers, and computer network architects, and workers in these occupation groups could afford more than half the city’s rentals in 2023. By contrast, New Yorkers making average wages as web developers and computer support specialists could afford less than 5%.

Low, Medium, and High-Density Districts

We follow the 10 basic residence districts, R1 through R10, as designated by the current NYC Zoning Resolution, including contextual districts in each group. Low-density zoning districts (R1-R5) typically allow one and two-family houses, as well as low-density multifamily buildings with typically fewer than five units. R6 through R8 districts allow medium-density apartment buildings. R9 and R10 districts allow high-rise buildings and are often found in high-density neighborhoods in Manhattan.

Developable Lots

We define developable lots as those that are not under or surrounded by water or too narrow to accommodate a building. According to the current Zoning Resolution, the minimum lot width for the most dense residential district is 18 feet, with wider minimum requirements for less dense districts. We assume developable lots can be combined to create larger lots. Lots that are currently under public use such as highways, parks, and schools are not considered developable in our report.

Neighborhood-Based Adaptive Zoning Reform Near Public Transit

The current zoning makes building medium-density apartments difficult, even though construction costs for smaller and mid-sized apartment buildings tend to be less than those for high-rises. Our research shows that allowing underutilized residential areas within walking distance of public transit in the outer boroughs, to catch up with more dense buildings that already exist in the same area, would unlock opportunities to create up to 1.1 million more homes.

To arrive at this number, we started by identifying sites in “transit-rich” areas within walking distance (0.5-mile radius) of the MTA subway, Long Island Rail Road, and Metro-North Railroad stations. Within this area, we excluded any sites that are designated as residential but used for public transit and utility infrastructure, public institutions such as hospitals and schools, and public recreational space. In addition, we excluded landmarks and historic districts designated by the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, lots that are too narrow to accommodate any building, and lots owned by the U.S. National Park Service, state and city agencies, or the MTA.

We then removed areas that are at higher risk of a 100-year flood due to rising sea levels by the 2050s, based on data from the Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability on behalf of the CUNY Institute for Sustainable Cities and the New York Panel on Climate Change.

Finally, among the sites that remained after applying these filters, we identified those that are zoned as low and medium-density but are either vacant or occupied by one-family or two-family houses. We then calculated the increase in housing capacity if these underutilized areas were rezoned only to a degree that is no denser than larger residential buildings that already exist in the transit-rich part of each area. This adaptive approach allows under-developed, low-density areas near mass public transit in outer boroughs to catch up with the denser parts of each area, without meaningfully changing the fabric of each neighborhood. ◼

About StreetEasy

StreetEasy is reimagining how people buy, sell, and rent homes across New York City and New Jersey. Used more than any other local real estate platform, StreetEasy’s website and mobile apps provide vetted and verified listings, plus intuitive search tools and data-driven content to help people unlock the opportunity of living here. Based in NYC, our workplace culture reflects who we are: Everyone should live in a world where they feel valued and supported.

StreetEasy, launched in 2006 and based in Manhattan, is owned and operated by Zillow Group (NASDAQ: Z and ZG) and is a registered trademark of Zillow, Inc.

About Tech:NYC

Tech:NYC is an engaged network of technology leaders working to foster a dynamic, diverse, and creative New York. The organization works with policymakers and business leaders to support a successful technology ecosystem, attract and retain talent, and celebrate New York and the companies that call it home. Tech:NYC represents more than 800 New York tech companies.

StreetEasy is an assumed name of Zillow, Inc. which has a real estate brokerage license in all 50 states and D.C. See real estate licenses. All data for uncited sources in this presentation has been sourced from Zillow data. All third-party product, company names and logos are trademarks of their respective holders and use of them does not imply any affiliation. Copyright © 2024 by Zillow, Inc. and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved.