The names of Lower Manhattan streets like Maiden Lane NYC and Broad Street hint at their long histories.

Ever wonder about the story behind streets like Maiden Lane NYC? In Lower Manhattan, traces of New York City’s storied past can be gleaned from its street names — unlike farther uptown, where they are hidden behind numbers.

Broad Street was the widest street in the area other than Broadway, and it got that way because tall-masted Dutch ships once sailed down a waterway in the middle called the Heere Graft. That waterway was filled in by the 1700s, leaving an especially wide roadway. Old Slip, Peck Slip and Market Slip were once waterways where ships “slipped in” to dock. Meanwhile, Bridge Street crossed the Broad Street canal, and Wall Street was built to keep marauding Brits and Indians out — though in fact, they never materialized. Here are five of the more unusual street names in Lower Manhattan, and the stories behind them.

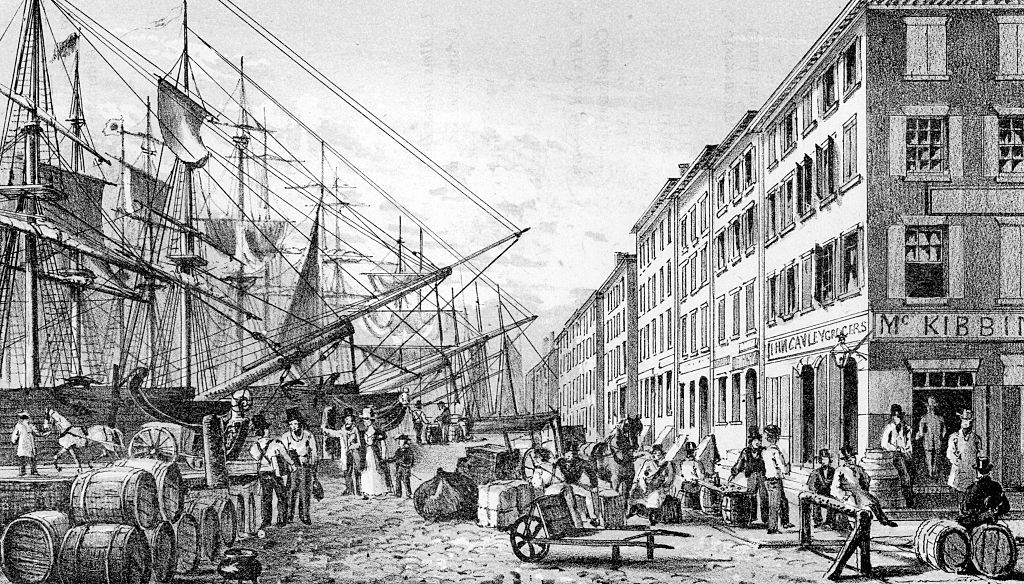

An etching from a painting titled “View of South Street, from Maiden Lane NYC,” 1828. From the New York Public Library. (Photo by Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images).

Maiden Lane NYC

Maiden Lane NYC runs from Broadway at Cortlandt Street east and southeast to South Street. Its curving course marks the spot of a former waterway. It’s one of the oldest street names in Lower Manhattan, appearing on maps in English in the late 1600s. Even before the British takeover in 1664, it was called Maagde Paetje in Dutch; the meaning was the same. While many accounts have Maiden Lane named for a tree-lined path when couples wandered in romantic reverie, a more prosaic story says that girls and young women from Dutch households would wash the family clothing in the fresh water brook that used to flow here. The path of the street recalls its course, as does the name, which has proven quite durable. For example, surrounding streets such as Crown, King, Queen and Princess became Liberty, Pine, Pearl, and part of Beaver after the Brits were kicked out of NYC in 1783.

Marketfield Street in Lower Manhattan. (Source: Zach/Wikimedia Commons, CC)

Marketfield Street

One of the obscurer streets in lower Manhattan, this is also one of the few L-shaped streets on the island. It changes directions at its halfway point, running from Beaver and New Streets south, then east to Broad Street; Commerce Street in Greenwich Village is another such street with an “elbow.”

The street is an English transliteration of the Dutch marktveldt, or “market-field.” Before lawn bowling became a craze in the Dutch colonial days, a produce and livestock market was located at Bowling Green and this street once ran past it, becoming Battery Place further west. After the British took over, the street was also occasionally known as Petticoat Lane. In the past it has also been named Exchange Street, Field Street, Fieldmarket Street and Oblique Road.

New Amsterdam’s first French Huguenot church was built on the narrow lane in 1688, between what is now Whitehall and Broadway. This part of Marketfield Street is no longer there; it was eliminated by the construction of the since-razed NYC Produce Exchange between 1882 and 1884.

Beaver Street today is in the heart of the Financial District — fitting, since many early New Yorkers made their fortunes selling beaver pelts.

Beaver Street

One of Manhattan’s oldest streets was named very early on, in the 1660s, and commemorates the paddle-tailed, dam-building, aquatic rodent whose pelts made up the chief avenue of commerce between Dutch settlers and the already established Native Americans during New Amsterdam’s earliest days from the 1620s through the 1650s.

Even after sales of beaver pelts fell off, the animals continued to be much prized for centuries, so much so that the wealthiest man in America during his time, John Jacob Astor, made his fortune on beaver fur. Representations of the beaver are seen in the official seal of New York City, and, of course, terra cotta beavers can be seen in the Astor Place station of the 6 train, which is named for John Jacob.

Beaver Street runs from Whitehall Street at Bowling Green east to Pearl Street just south of Wall. For much of the colonial era and afterward, Beaver Street ran between just Bowling Green and Broad Street. The block between Broad and William was variously called Prince or Princess Street, depending on spelling and the whim of the mapmaker, and there was just an L-shaped section between William and Pearl. According to the invaluable resource of Gil Tauber’s Old Streets, this was a short lane called Slote, or Sloat, Street, named for the Dutch sloot, or drainage ditch, which we can guess was pretty much its original purpose. After 1807, Sloat became Exchange and later, Merchant Street. Finally, after 1835, Beaver Street was extended to its present length and the remaining section of Merchant Street was then called Hanover Street.

Coenties Slip and Alley

There probably isn’t another street in the USA named “Coenties,” but in Lower Manhattan, we have two. So there. Herman Melville mentions Coenties Slip in “Moby-Dick,” Chapter 1:

Circumambulate the city of a dreamy Sabbath afternoon. Go from Corlears Hook to Coenties Slip, and from thence, by Whitehall, northward. What do you see? Posted like silent sentinels all around the town, stand thousands upon thousands of mortal men fixed in ocean reveries.

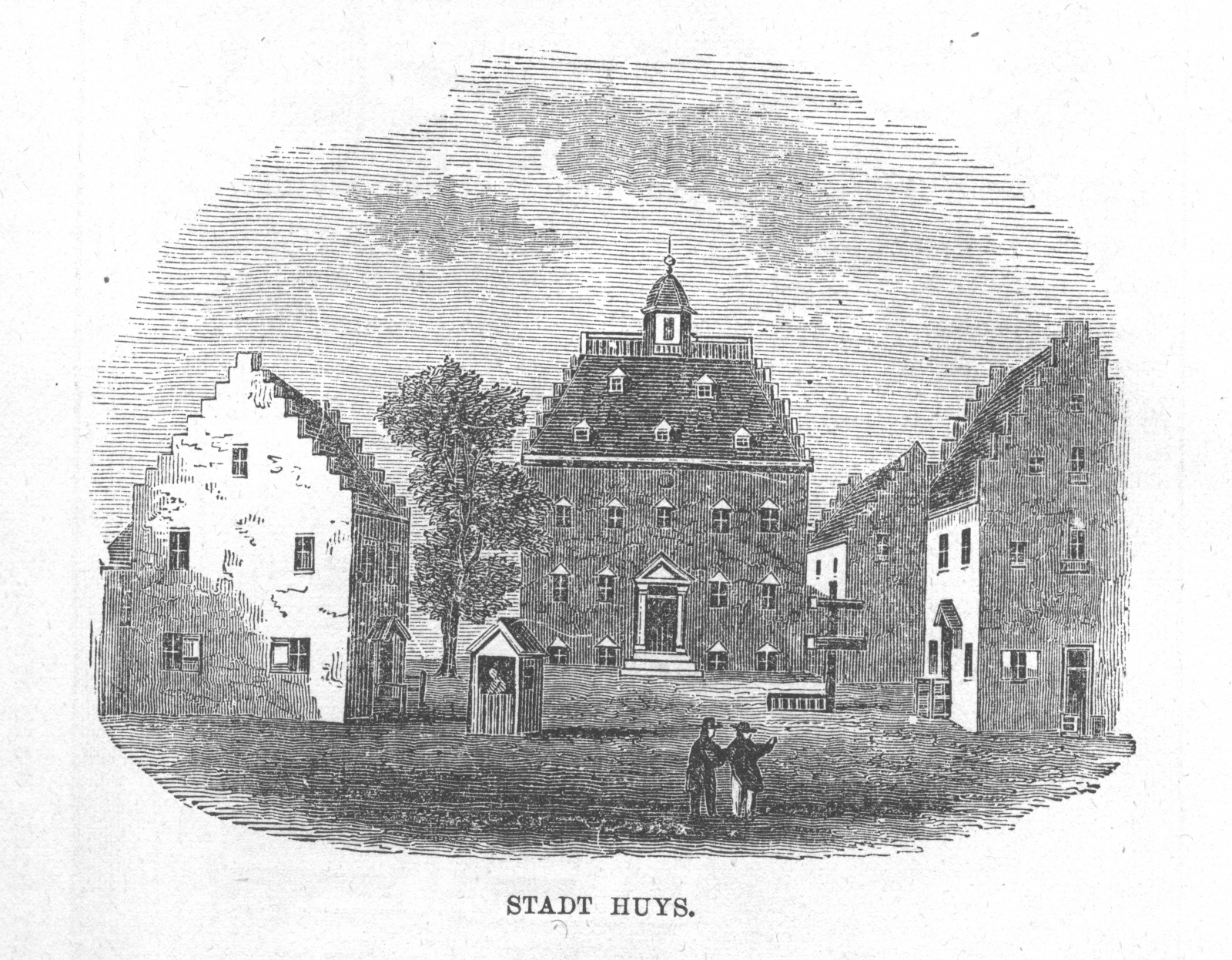

Coenties Slip, which extends opposite Coenties Alley between Pearl and South Streets, was one of the largest of lower Manhattan’s boat “slips.” It has pretty much kept its old slanted shape, too. The slip was filled in around 1870. In the background looms 85 Broad Street, the present NYC home of Goldman Sachs, built in 1983. It demolished part of Stone Street, which prompted the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission to protect the original Dutch street layout in lower Manhattan. The building at 85 Broad stands where the seat of Dutch colonial government, the Stadt Huys, or State House, used to be. Archeological remnants of the neighboring Lovelace Tavern are still there.

An engraving of the “Stadt Huys,” or Dutch state house, at the corner of Coenties Slip and Pearl Street in New York City (then New Amsterdam) from an 1874 book. (Source: Interim Archives/Getty Images)

The name “Coenties” is old Dutch as Dutch can be, since it recalls an early landowner from the New Netherlands era, Conraet Ten Eyck, a tanner and shoemaker. He was nicknamed Coentje, or “Coonchy” to the British, and over time settled into this spelling. Ten Eyck Street in Brooklyn’s East Williamsburg was also named for him. Another story has it that the name is a contraction of “Conraet’s and Antje’s”— Conraet Ten Eyck and his wife Antje. Ten Eyck in Dutch means “The Oaks.”

Zuccotti Park, where Occupy Wall Street was launched, sits on what was Temple Street. A sign still marks the street.

Temple Street

One of lower Manhattan’s more intriguingly named streets isn’t even there, though the city continues to mark it with a sign.

Temple Street ran for just one block, from Cedar north to Liberty. It had been reduced to one block from two in 1907, when the Trinity and U.S. Realty Buildings, both tall Gothic towers built to complement Trinity Church, were constructed on both sides of Thames Street.

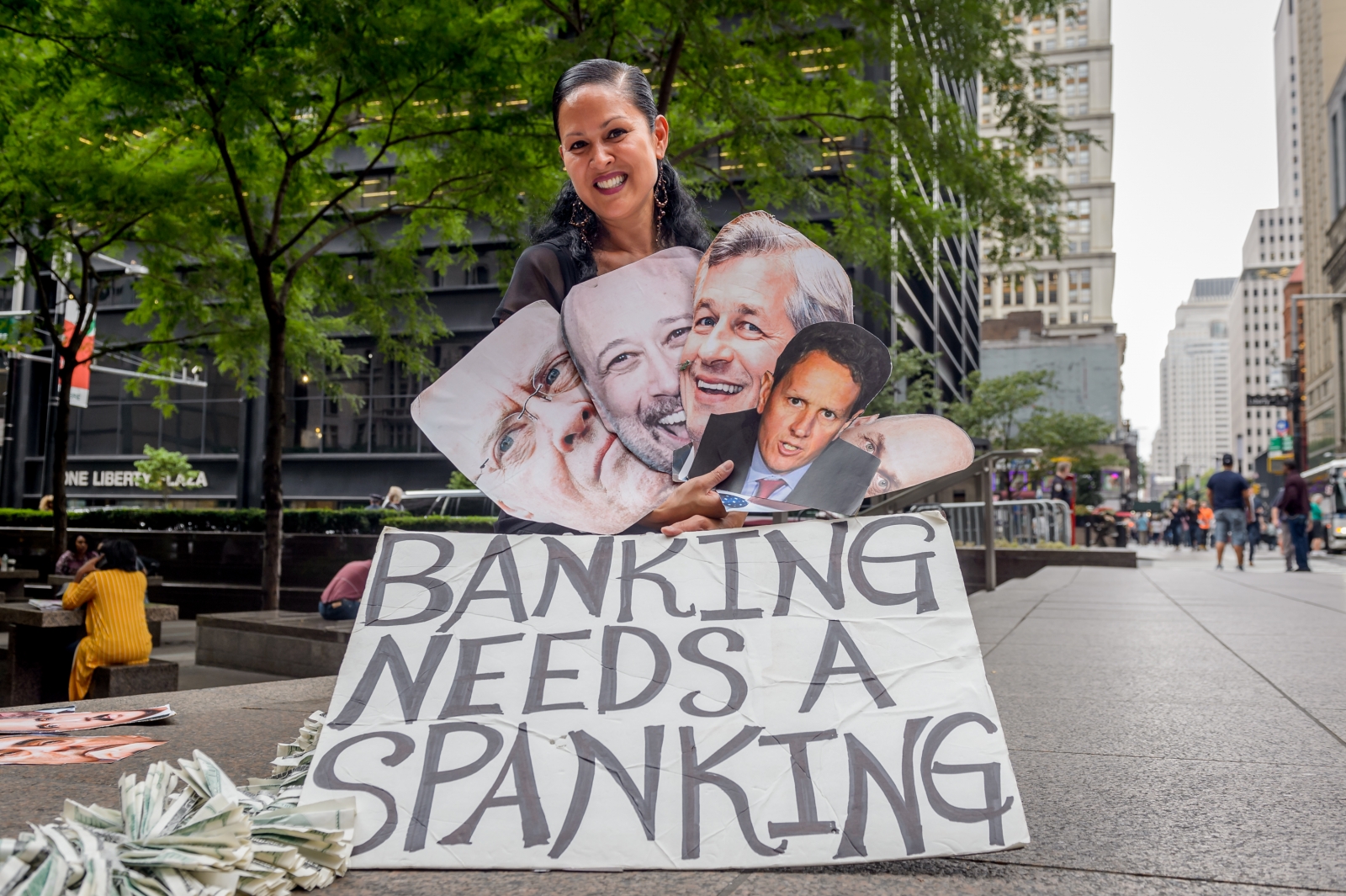

In 1967, it was decided that Ernest Flagg’s 1908 Beaux Arts skyscraper Singer Tower, one of the most identifiable buildings in the Manhattan skyline on Liberty and Broadway, should come down. The forbidding U.S. Steel Building, later renamed One Liberty Plaza, was constructed in its place, opening in 1973. The small parcel across the street between Broadway, Trinity Place, Cedar Street and Liberty Street became Liberty Plaza Park, and the last piece of Temple Street was eliminated.

Liberty Plaza Park, later renamed Zuccotti Park, was affected greatly by the destruction of the World Trade Center a block away in 2001, and it was used for months thereafter as a staging area for emergency vehicles and equipment. Formerly a large, relatively shade-free concrete plaza, the park was given a rehabilitation in 2006-2007 when dozens of honey locust trees were planted and new fluorescent lighting was installed under the pavements, in an unusual arrangement.

Later, Zuccotti Park was the base camp for Occupy Wall Street‘s protest against economic inequality.

Today, the sign is all that remains of Temple Street.

Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens.

—

Hey, why not like StreetEasy on Facebook and follow @streeteasy on Instagram?