As in many cities across the U.S., rapidly rising rent prices and stagnant incomes have made New York City highly unaffordable for many renters. According to StreetEasy’s new estimates, a typical New York household will spend 58.4 percent of its income on rent in 2015; the rent burden is even greater in some neighborhoods. In the Lower East Side, for example, the median asking rent eats up more than 80 percent of current residents’ median income.

A growing rent burden has consequences for all current and future New Yorkers. For existing renters, the obvious consequence is that living in New York City is less affordable. A greater share of a renter’s income is consumed by housing costs, which could place them in greater financial vulnerability. For non-renters, the consequences of a heavily burdened rental population play out in the greater New York economy. With less disposable income, renters may choose to curb their spending on eating out, going to Broadway shows, and other activities that drive the city’s economy. In the long term, high rent costs make New York City less competitive in the global race for new and highly skilled people. When considering job offers in Austin, Seattle, Toronto or New York City, for example, affordability may be the deciding factor for an individual. Attracting people with big ideas and energy from around the world is the lifeblood of New York City, but housing affordability may be dimming that beacon.

Ensuring New York is an affordable place to live is important to the city’s long-term economic health, so what exactly is being done about it? Efforts to improve affordability generally fall into two categories: providing incentives and subsidies to build or preserve affordable units and easing zoning regulations to allow the market to respond naturally.

Inducing supply through tax incentives

One of the most important incentives to promote the addition of affordable rental apartments in New York City comes in the form of a tax credit. The 421-a tax incentive program was created in 1971, a period in which New York City was reeling from mass population outflow to the suburbs and was on the brink of bankruptcy. With crime on the rise and the city’s economy in jeopardy, policymakers sought a way to encourage developers of residential real estate to construct new units in the city that would meet certain affordability requirements. The early promise of the 421-a tax incentive program was the creation of affordable units that may not have otherwise been built.

The program’s cost — $1.1 billion in fiscal year 2013 — is often cited in arguing that the program is an inefficient and ineffective use of public funds. Critics argue that the program does more to encourage market-rate development than affordable housing, and that public funds would be better used by directly funding the construction of affordable housing.

While its merits can be debated, the program’s significant footprint on the city’s real estate market cannot. According to the New York City Department of Finance, more than 152,000 units have been created in buildings with a 421-a exemption – roughly three times the number of units constructed citywide in the last three years[1]. The program is set to expire this year, sparking a citywide conversation about the future of supply growth led by tax incentives, with developers arguing that the program is necessary to justify the cost of providing affordable units. Opponents argue that direct funding of affordable units would have a far greater impact.

Rezoning to boost housing stock

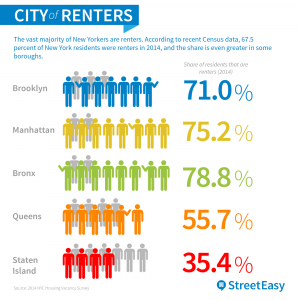

Affordable housing is a perennial hot topic in New York City mayoral campaigns, and for a good reason: this is a city of renters. The share of New Yorkers that rent reached 67.5 percent in 2014 according to recent Census data. The share was even greater in the Bronx (78.8 percent), Manhattan (75.2 percent) and Brooklyn (71.0 percent) [2]. By comparison, just 36.5 percent of Americans rented in 2013. So central is the monthly rent check to the New York experience that the first three questions often asked upon meeting a new person are: “What’s your name?” “Where do you live?” and “What is your rent?”

Shortly after being elected in 2013, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio unveiled his 10-year housing plan, which outlines an ambitious goal of constructing and preserving 200,000 affordable housing units over 10 years[3]. In his opening sentence, Mayor de Blasio puts it bluntly, “We have a crisis of affordability on our hands.”

Chief among the mayor’s housing proposals is mandatory inclusionary zoning, which would require developers of new buildings to include affordable units. Currently, the city allows up to a 33 percent density bonus for a new building if at least 20 percent of units are made affordable for up to 35 years on a voluntary basis[4]. A density bonus is attractive to a developer because it allows for additional units to be built than zoning restrictions allow, thus aiding in the project’s bottom line.

The mayor identified six areas in the city to pilot mandatory inclusionary zoning: East New York, Long Island City, the Jerome Avenue Corridor in the Bronx (located in the Concourse neighborhood), Flushing West, the Bay Street Corridor in Staten Island (located in the Stapleton neighborhood), and East Harlem. StreetEasy’s projected 2015 rent-to-income ratios suggest that renting in these neighborhoods will be particularly unaffordable this year. In all of the proposed pilot areas, new households will spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent in 2015. In 5 of the 6 areas, renters will spend more than half of their income.

| Neighborhood | Median Asking Rent (2015) | Rent-to-Income Ratio (2015) |

| East New York, Brooklyn | $1,598 | 55.1% |

| Long Island City, Queens | $2,756 | 59.2% |

| Concourse, Bronx | $1,462 | 55.9% |

| Flushing, Queens | $1,825 | 38.0% |

| East Harlem, Manhattan | $2,078 | 81.8% |

*Note: Sufficient rental data was not available for the Bay Street Corridor in Staten Island and was therefore omitted from this analysis.

Modernizing regulations to promote growth

Ultimately, New York City’s affordability problem is rooted in the lack of adequate supply of rental housing. According to recent Census data, the rental vacancy rate was just 3.45 percent in 2014 – less than 1 percent greater than in 2011. The situation is even worse for renters seeking lower-priced rentals. The vacancy rate for apartments priced below $800 was just 1.8 percent in 2014. The dangerously low vacancy rates speak to the dramatic imbalance between the demand for housing and what is available to rent.

High construction costs in New York City, restrictive zoning laws that limit new construction, and the difficulty of securing financing are three key reasons why supply continues to lag behind demand. In late February the city’s Planning Department announced a proposal to modernize zoning regulations to encourage new construction of affordable housing[5]. Among the proposed changes is the elimination of minimum parking requirements for new affordable units. Parking facilities can add a significant cost to the construction of new housing, which is often passed on to residents through higher rents or sales prices. Recent research from UCLA estimates that a single underground parking spot costs $35,000 to build in New York City, which likely understates the costs in extremely dense areas of the city where land values are highest[6]. By that estimate, a new 100-unit building in Brooklyn would carry $1.19 million in additional costs for required parking alone.

Parking requirements may make some new developments unprofitable, meaning developers will simply forgo the project altogether. With the city’s rental supply as constricted as it is, we cannot afford to waste any opportunity to bring more units to the market.

The takeaway

The direction and growth of the city will depend ultimately upon its voters and policy makers – balancing the desire to keep New York City a beacon for all who wish to make it here and the necessity of allowing change, growth and affordable housing. There is no ‘silver bullet’ that will solve New York City’s housing affordability crisis. Rather, the city’s leaders will need to draw from a multitude of policies – from zoning regulations to tax incentives – that will spur growth and target affordable housing to those who need it.

Endnotes

[1] Housing Vacancy Survey 2014

[2] 2013 ACS 1-year estimates

[3] http://www.nyc.gov/html/housing/assets/downloads/pdf/housing_plan.pdf

[4] http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/zone/zh_inclu_housing.shtml

[5] http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/pdf/zoning-qa/affordable-housing.pdf

[6] http://shoup.bol.ucla.edu/HighCost.pdf